- Dutch1

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

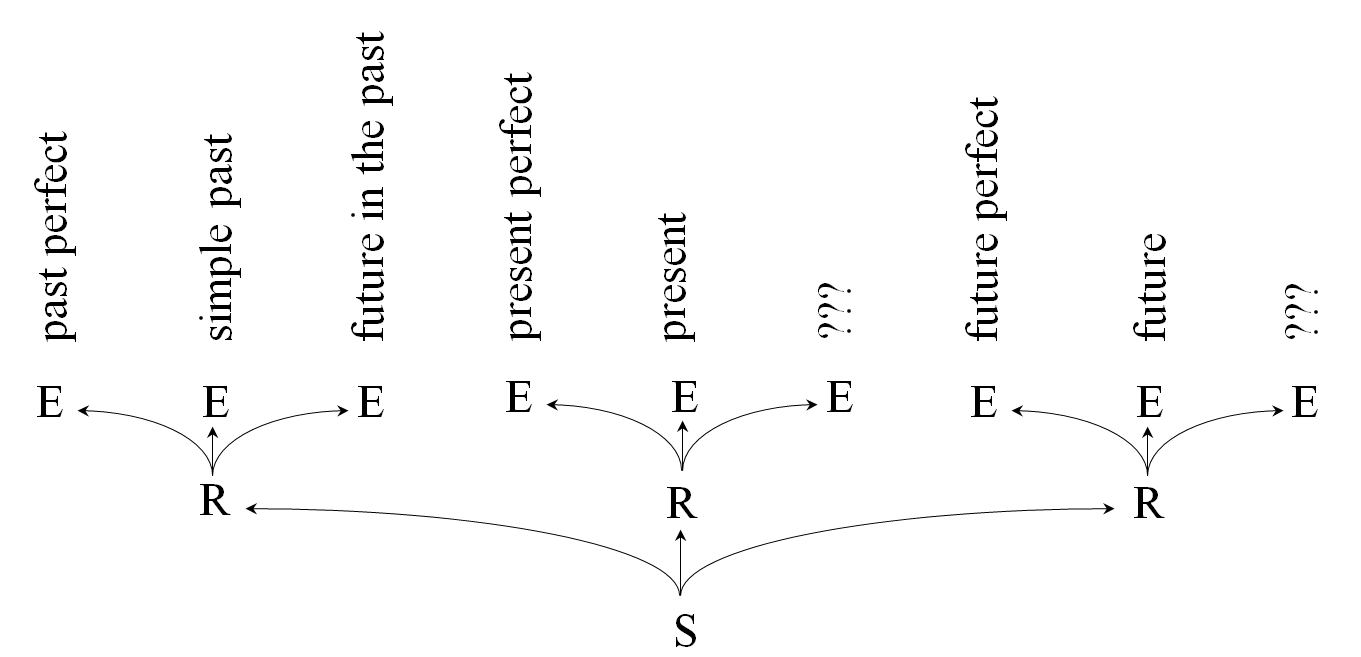

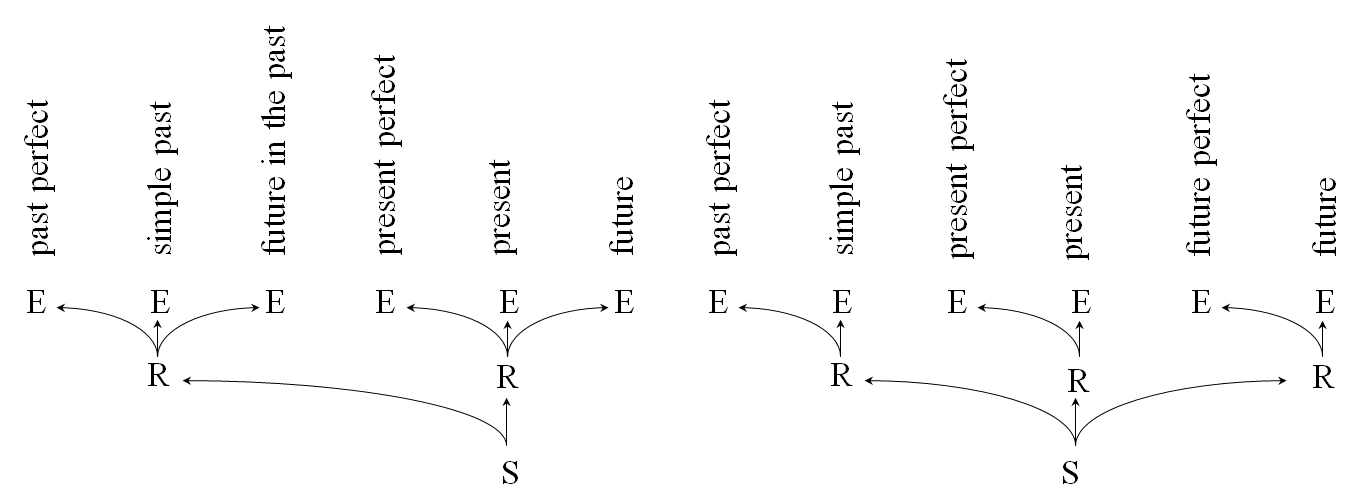

This section discusses the binary tense system originally proposed by Te Winkel (1866) and briefly outlined above, which is based on three binary oppositions: present versus past, imperfect versus perfect, and non-future versus future. Te Winkel was not so much concerned with the properties ascribed to time in physics or in philosophy, which heavily influenced the currently dominant view that follows Reichenbach's (1947) seminal work, which is based on two ternary oppositions: (i) past—present—future and (ii) anterior-simultaneous-posterior. Instead, Te Winkel had a (surprisingly modern) mentalistic view on the study of language, and was mainly interested in the properties of time as encoded in the tense systems found in natural language. Verkuyl (2008:ch.1) compared the two systems and argued that Te Winkel's system is more successful in describing the universal properties of tense than the Reichenbachian systems for reasons that we will review after we have discussed the details of Te Winkel/Verkuyl's binary approach.

- I. Binary tense theory: time from a linguistic perspective

- II. A comparison with Reichenbachʼs approach

- III. Conclusion

Verkuyl (2008) refers to Te Winkel's (1866) proposal as the binary tense system, given that the crucial distinctions proposed by Te Winkel can be expressed by means of the three binary features in (229).

| a. | ±past: present versus past |

| b. | ±posterior: future versus non-future |

| c. | ±perfect: imperfect versus perfect |

The three binary features in (229) define eight different tenses, which are illustrated in Table 9 by means of examples in the first person singular form.

| present | past | ||

| synchronous | imperfect | simple present Ik wandel. I walk | simple past Ik wandelde. I walked |

| perfect | present perfect Ik heb gewandeld. I have walked | past perfect Ik had gewandeld. I had walked | |

| posterior | imperfect | future Ik zal wandelen. I will walk | future in the past Ik zou wandelen. I would walk |

| perfect | future perfect Ik zal hebben gewandeld. I will have walked | future perfect in the past Ik zou hebben gewandeld. I would have walked | |

The features in (229) are in need of some further explication, which will be given in the following subsections. For clarity of presentation, we will focus on the temporal interpretations cross-linguistically attributed to the tenses in Table 9 and postpone discussion of the more special temporal and the non-temporal aspects of their interpretations in Dutch to, respectively, Section 1.5.2 and Section 1.5.4.

Binary Tense theory crucially differs from the Reichenbachian approaches in that it does not identify the notion of present with the notion of speech time. Keeping the notions of speech time and present strictly apart turns out to offer important advantages. For example, it allows us to treat tense as part of a developing discourse: shifting of the speech time does not necessarily lead to shifting of the present. In a binary system, the present tense can be seen as not referring to the speech time n but to some larger temporal domain i that includesn. The basic idea is that the use of the present-tense form signals that the speaker is speaking about eventualities as occurring in his or her present even though these eventualities need not occur at the point of speech itself. This can be illustrated by the fact that a speaker could utter an example such as (230a) on Tuesday to express that he is dedicating the whole week (that is, the stretch of time from Monday till Sunday) to writing the section on the tense system mentioned in (230a). It is also evident from the fact that this example can be followed in discourse by the utterances in (230b-d), which subdivide the present-tense interval evoked by the adverbial phrase deze week'this week' in (230a) into smaller subparts.

| a. | Ik | werk | deze week | aan de paragraaf | over het tempussysteem. | present | |

| I | work | this week | on the section | about the tense system | |||

| 'This week, Iʼm working on the section on the tense system.' | |||||||

| b. | Gisteren | heb | ik | de algemene opbouw | vastgesteld. | present perfect | |

| yesterday | have | I | the overall organization | prt.-determined | |||

| 'Yesterday, I determined the overall organization.' | |||||||

| c. | Vandaag | schrijf | ik | de inleiding. | simple present | |

| today | write | I | the introduction | |||

| 'Today, Iʼm writing the introduction.' | ||||||

| d. | Daarna | zal | ik | de acht temporele vormen | beschrijven. | future | |

| after.that | will | I | the eight tense forms | describe | |||

| 'After that, I will describe the eight tense forms.' | |||||||

| e. | Ik | zal | het | zaterdag | wel | voltooid | hebben. | future perfect | |

| I | will | it | Saturday | prt. | completed | have | |||

| 'I probably will have finished it on Saturday.' | |||||||||

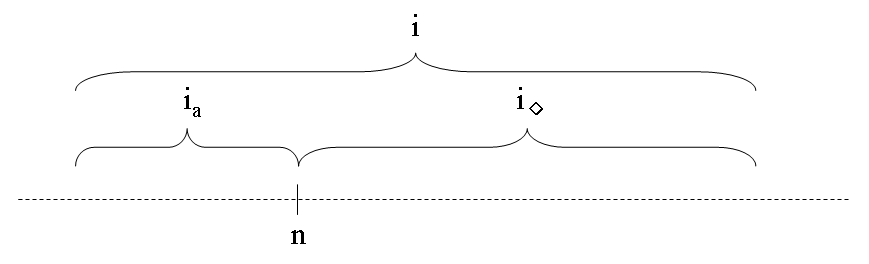

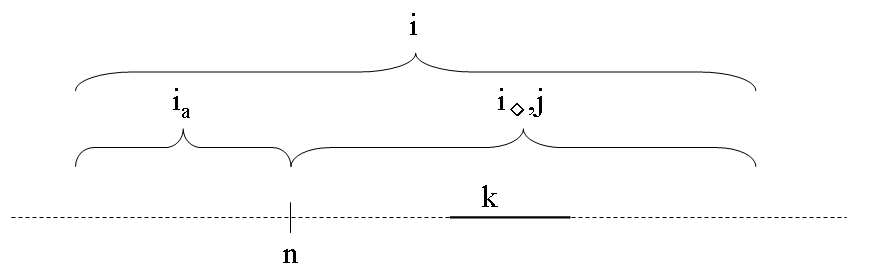

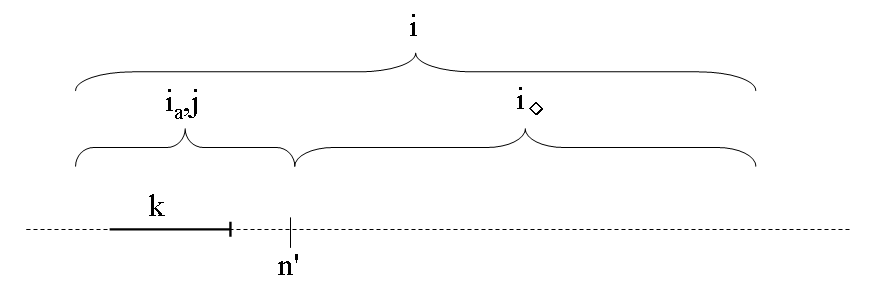

The sequence of utterances in (230) thus shows that what counts as the present for the speaker/hearer constitutes a temporal domain that consists of several subdomains, each of them denoted by a temporal adverbial phrase that locates the four eventualities expressed by (230b-e) more precisely within the interval denoted by deze week'this week' in (230a). Following Verkuyl (2008) the global structure of a present domain is depicted in Figure 6, in which the dotted line represents the time line, n stands for the speech time, and i for the time interval that is construed as the present for the speaker/hearer. The role of the rightward shifting speech time n is to split the present-tense intervali into an actualized part ia (the present preceding n) and a non-actualized part i◊ (the present following n).

It is important to realize that present-tense interval i is contextually determined. In the discourse chunk in (230), it may seem as if the present i is defined by the adverbial phrase deze week'this week', but (231) shows that the present-tense interval can readily be stretched by embedding (230a) in a larger story in the present tense.

| We werken nu al jaren aan een grammatica van het Nederlands. De eerste delen zijn al afgerond en we beginnen nu aan het deel over het werkwoord. Deze week werk ik aan de paragraaf over het temporele systeem. [continue as in (230b-d)]We werken nu al jaren aan een grammatica van het Nederlands. De eerste delen zijn al afgerond en we beginnen nu aan het deel over het werkwoord. Deze week werk ik aan de paragraaf over het temporele systeem. [continue as in (230b-d)] | ||||

| 'We have been working for years on a grammar of Dutch. The first volumes are already finished and we are beginning now with the part on verbs. This week I am working on the section on the tense system. [....]' | ||||

Example (232) in fact shows that we can stretch the present-tense interval i indefinitely, given that this sentence involves an eternal or perhaps even everlasting present.

| Sinds de oerknal | breidt | het heelal | zich | in alle richtingen | uit | en | waarschijnlijk | zal | dat | voortduren | tot het einde der tijden. | ||

| since the Big Bang | expands | the universe | refl | in all directions | prt. | and | probably | will | that | continue | until the end thegen times | ||

| 'Since the Big Bang the universe is expanding in all directions and probably that will continue until the end of time.' | |||||||||||||

Ultimately, it is the shared extra-linguistic knowledge of the speaker and the hearer that determines what counts as the present-tense interval, and, consequently, which eventualities can be discussed by using present-tense forms. This was already pointed out by Janssen (1983) by means of examples such as (233); the extent of the presumed present-tense interval is determined (i) by the difference between the lifespan of, respectively, planets and human individuals, and (ii) by the fact that "being a stutterer" and "being ill" are normally construed as, respectively, an individual-level and a stage-level predicate.

| a. | De aarde is rond. | |

| the earth is round |

| b. | Jan is een stotteraar. | |

| Jan is a stutterer |

| c. | Jan is ziek. | |

| Jan is ill |

Following Verkuyl (2008), we can define Te Winkel's binary oppositions by means of the indices i and n, which were introduced previously, and the indices j and k, which pertain to the temporal location of the eventuality (state of affairs) denoted by the main verb, or, rather, the lexical projection of this verb. We have already mentioned that the defining property of the present domain is that it includes speech time n, which is expressed in (234a) by means of the connector "○". Verkuyl assumes that the present differs from the past in that past-tense interval i precedes speech time n, as indicated in (234b); we will see in Subsection C, however, that there are reasons not to follow this assumption.

| a. | Present: i ○ n | i includes speech time n |

| b. | Past: i < n | i precedes speech time n |

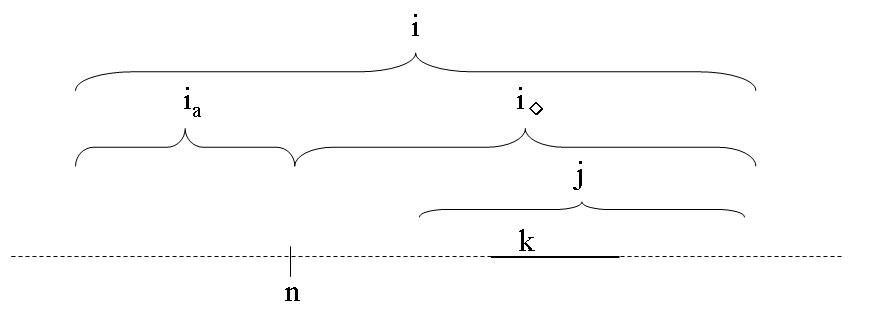

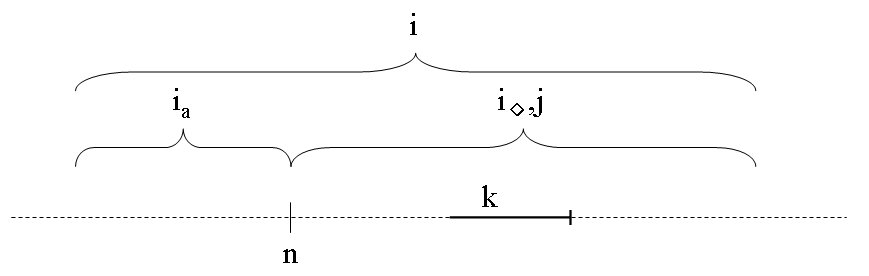

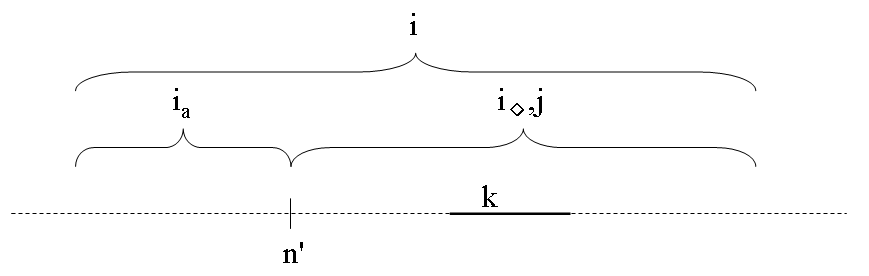

The index j will be taken as the temporal domain in which eventuality k is located. In other words, every eventuality k has not only its running time, but it has also its own present j, which may vary depending on the way we talk about it. In the examples in (230), for instance, the location of the present j of k is indicated by means of adverbial phrases; in example (230d), for instance, the adverbial phrase daarna restricts j to the time interval following Tuesday, and the semantic representation of (230d) is therefore as schematically indicated in Figure 7, in which the line below k indicates the actual running time of the eventuality.

It is important to note that, due to the use of the present-tense form in (230d), the notion of future is to be reduced to the relation of posteriority within the present domain. The difference between non-future and future is that in the former case the present j of eventuality k can synchronize with any subpart of i, whereas in the latter case it cannot synchronize with any subpart of the actualized part of the present, that is, it must be situated in the non-actualized part i◊ of what counts as the present for the speaker/hearer. This is expressed in (235) by means of the connectors "≈" and "<".

| a. | Non-future: i ≈ j | i and j synchronize |

| b. | Future: ia < j | ia precedes j |

The difference between imperfect and perfect tense pertains to the relation between eventuality k and its present j. In the latter case k is presented as completed within j, whereas in the former case it is left indeterminate whether or not k is completed within j. Or, to say it somewhat differently, the perfect presents k as a discrete, bounded unit, whereas the imperfect does not. This is expressed in (236) by means of the connectors "≼" and "≺".

| a. | imperfect: k ≼ j | k need not be completed within j |

| b. | Perfect: k ≺ j | k is completed within j |

The following subsections will show that the four present tenses in Table 9 in the introduction to this subsection differ with respect to (i) the location of eventuality k denoted by the lexical projection of the main verb within present-tense interval i, and (ii) whether or not it is presented as completed within its own present-tense interval j. Recall that we will focus on the temporal interpretations cross-linguistically attributed to the tenses in Table 9 and postpone the discussion of the more special temporal and the non-temporal aspects of their interpretations in Dutch to Section 1.5.4.

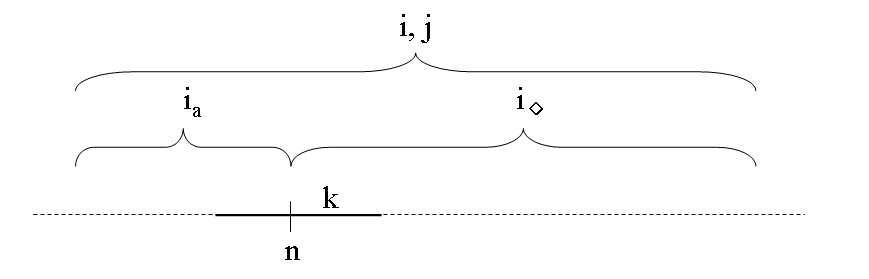

The simple present expresses that eventuality k takes place during present-tense interval i. This can be represented by means of Figure 8, in which index j is taken to be synchronous to the present i of the speaker/hearer (j = i) by default. The continuous part of the line below k indicates that the preferred reading of an example such as Ik wandel'I am walking' is that eventuality k overlaps with the moment of speech n.

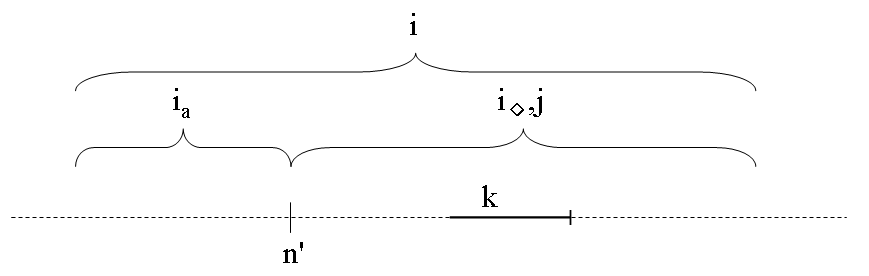

In many languages, including Dutch, the implication that k holds at the moment of speech n can readily be canceled by means of, e.g., adverbial modification: the simple present example (237) with the adverbial phrase morgen'tomorrow' can be used to refer to some future eventuality k.

| Ik | wandel | morgen. | ||

| I | walk | tomorrow | ||

| 'Iʼll walk tomorrow.' | ||||

This is, of course, to be expected on the basis of the definition of present in (234a), which states that the present-tense interval i must include speech time n, but does not impose any restrictions on j or k. Although we will briefly return to this issue in Subsection 5, we will postpone a more thorough discussion of this to Section 1.5.4, where we will show that this use of the simple present is a characteristic property of languages that do not express the future within the verbal tense system but by other means, such as adverbials.

The default reading of the present perfect is that eventuality k takes place before speech time n, that is, eventuality k is located in the actualized part of the present-tense interval ia (j = ia). In addition, the present perfect presents eventuality k as a discrete, bounded unit that is completed within time interval j that therefore cannot be continued after n; this is represented in Figure 9 by means of the short vertical line after the continuous line below k.

A sentence like Ik heb gisteren gewandeld'I walked yesterday' can now be fully understood: since neither the definition of present in (234a) nor the definition of perfect in (236b) imposes any restriction on the location of j (or k) with respect to n, the adverb gisteren'yesterday' may be analyzed as an identifier of jon the assumption that yesterday is part of a larger present-tense interval i that includes speech time n. This explains the possibility of using the present-tense form heeft'has' together with an adverbial phrase referring to a time interval preceding n.

In many languages, including Dutch, the implication that k takes place before speech time n can readily be canceled by means of, e.g., adverbial modification: the present perfect example (238) with the adverb morgen'tomorrow' can be used to refer to some future eventuality k. Again, this is to be expected given that neither the definition of present in (234a) nor the definition of perfect in (236b) imposes any restriction on the location of j (or k) with respect to n; we will return to this issue in Section 1.5.4.

| Ik | heb | je paper | morgen | zeker | gelezen. | ||

| I | have | your paper | tomorrow | certainly | read | ||

| 'Iʼll certainly have read your paper by tomorrow.' | |||||||

In the literature there is extensive discussion about whether perfect-tense constructions should be considered temporal or aspectual in nature. The position that individual linguists take often depends on the specific tense and aspectual theory they endorse. Since the characterization of the perfect tense in the binary (and the Reichenbachian) tense theory does not appeal to the internal temporal structure of the event, this allows us to adopt a non-aspectual view of the perfect tense. The non-aspectual view may also be supported by the fact that the use of the perfect tense does not affect the way in which the internal structuring of eventuality k is presented; it is rather the interaction of perfect tense and Aktionsart (inner aspect) that should be held responsible for that. This will become clear when we consider the contrast between the atelic (states and activities) and telic (accomplishments and achievements) eventualities in (239). We refer the reader to Section 1.2.3 for a discussion of the different kinds of Aktionsart.

| a. | Jan heeft | zijn hele leven | van Marie | gehouden. | state | |

| Jan has | always | of Marie | loved | |||

| 'Jan has loved Marie always.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan heeft | vanmorgen | aan zijn dissertatie | gewerkt. | activity | |

| Jan has | this.morning | on his dissertation | worked | |||

| 'Jan has worked on his PhD thesis all morning.' | ||||||

| c. | Jan is | vanmorgen | uit Amsterdam | vertrokken. | achievement | |

| Jan is | this.morning | from Amsterdam | left | |||

| 'Jan left Amsterdam this morning.' | ||||||

| d. | Jan heeft | de brief | vanmorgen | geschreven. | accomplishment | |

| Jan has | the letter | this.morning | written | |||

| 'Jan wrote the letter this morning.' | ||||||

All examples in (239) present the eventualities as autonomous units that (under the default reading) are completed at or before speech time n. This does not imply, however, that eventualities cannot be continued or resumed after n. This is in fact quite natural in the case of atelic verbs: an example such as (239a) does not entail that Jan will not love Marie after speech time n as is clear from the fact that it can readily be followed by ... en hij zal dat wel altijd blijven doen'and he will probably continue to do so forever'. Likewise, example (239b) does not imply that Jan will not continue his work on his thesis after speech time n as is clear from the fact that (239b) can readily be followed by ... en hij zal daar vanmiddag mee doorgaan'... and he will continue doing that in the afternoon'. The telic events in (239c&d), on the other hand, do imply that the events have reached their implied endpoint and can therefore not be continued after speech time n. The examples in (239) thus show that the internal temporal structure of the eventualities is not affected by the perfect tense but determined by the Aktionsart of the verbs/verbal projections in question. From this we conclude that the perfect is not aspectual in nature but part of the tense system; see Verkuyl (2008:20-27) for a more detailed discussion.

The future expresses that eventuality k takes place after speech time n, that is, eventuality k is located in the non-actualized part of the present-tense interval (j = i◊).

The implication of Figure 10 is that eventuality k cannot take place during ia, but example (240) shows that this implication can be readily cancelled in languages like Dutch. In fact, this will be one of the reasons for denying that willen functions as a future auxiliary in Dutch. We will return to this in Sections 1.5.2 and 1.5.4.

| Jan zal | je paper | lezen. | Misschien | heeft | hij | het | al | gedaan. | ||

| Jan will | your paper | read | maybe | has | he | it | already | done | ||

| 'Jan will read your paper. Maybe he has already done it. ' | ||||||||||

The interpretation of the future perfect is similar to that of the future, but differs in two ways: (i) it is not necessary that the eventuality k has started after n and (ii) it is implied that the state of affairs is completed before the time span i◊has come to an end.

The implication of Figure 11 is again that eventuality k cannot take place during ia, but example (241) shows that this implication can be readily cancelled in languages like Dutch by means of, e.g., adverbial modification. We will put this non-future reading aside for the moment but return to it in Sections 1.5.2 and 1.5.4.

| Jan zal | je paper | ondertussen | waarschijnlijk | wel | gelezen | hebben. | ||

| Jan will | your paper | by.now | probably | prt | read | have | ||

| 'Jan will probably have read your paper by now.' | ||||||||

The main difference between the future and the future perfect is that in the former the focus is on the progression of the eventuality (without taking into account its completion), whereas in the latter the focus is on the completion of the eventuality k in j. This difference is often somewhat subtle in the case of states and activities but transparent in the case of telic events. Whereas the future tense in example (242a) expresses that the process of melting will start or take place after speech time n, the future perfect example in (242b) simply expresses that the completion of the melting process will take place in some j that is positioned in i◊; the future perfect leaves entirely open whether the melting process started before, after or at n.

| a. | Het ijs | zal | vanavond | smelten. | |

| the ice | will | tonight | melt | ||

| 'The ice will melt tonight.' | |||||

| b. | Het ijs | zal | vanavond | gesmolten | zijn. | |

| the ice | will | tonight | melted | be | ||

| 'The ice will have melted tonight.' | ||||||

In (243), similar examples are given with the accomplishment die brief schrijven: (243a) places the entire eventuality after the time n, whereas (243b) does not seem to make any claim about the starting point of the eventuality but simply expresses that the eventuality will be completed after n (but within i◊).

| a. | Jan zal | vanavond | die brief | schrijven. | |

| Jan will | tonight | that letter | write | ||

| 'Jan will write that letter tonight.' | |||||

| b. | Jan zal | vanavond | die brief | geschreven | hebben. | |

| Jan will | tonight | that letter | written | have | ||

| 'Jan will have written that letter by tonight.' | ||||||

For the moment, we will ignore the difference between future and future perfect with respect to the starting point of the state of affairs, but we will return to this in Section 1.5.2, where we will challenge the claim that zullen is a future auxiliary.

In the tense representations given in the previous subsections, we made a distinction between the present i of the speaker/hearer, on the one hand, and the present j of eventuality k, on the other. Although the latter is always included in the former, it can readily be shown that the distinction need be made. This may not be so clear in examples such as (244a), in which j seems to synchronize with the entire present-tense interval i of the speaker/hearer. Adverbial phrases of time, however, may cause j to synchronize to a subpart of i: the adverb vandaag'today' in (244b) refers to a subpart of i that includes n, and morgen'tomorrow' in (244c) refers to a subpart of i situated ini◊.

| a. | We | zijn | thuis. | |

| we | are | at.home | ||

| 'We are at home.' | ||||

| b. | We | zijn | vandaag | thuis. | |

| we | are | today | at.home |

| c. | We | zijn | morgen | thuis. | |

| we | are | tomorrow | at.home |

That it is j and not the present-tense interval i that is affected by adverbial modification is also clear from the fact that it is possible to have present-tense examples such as (245), in which the two adverbial phrases refer to two subdomains within i.

| We | zijn | vandaag | thuis | en morgen | in Utrecht. | ||

| we | are | today | at.home | and tomorrow | in Utrecht |

Entailments are furthermore computed on the basis of j and not the present-tense interval i. Example (244b), in which j synchronizes with a subpart of i that includes n, does not say anything about the whereabouts of the speaker yesterday or tomorrow, even when these time intervals are construed as part of present-tense interval i. That entailments are computed on the basis of j and not i is even clearer in example (244c), in which j synchronizes with (a subpart of) i◊; this example does not say anything about the whereabouts of the speaker at speech time n, which clearly shows that the state of affairs does not have to hold during the complete present-tense interval i. It is only in cases such as (244a), without a temporal modifier, that we conclude (by default) that the state of affairs holds for the complete present-tense interval i.

The examples in (246) show that, like the present tense, the past tense involves some larger time interval, which can be divided into smaller subdomains. A speaker can utter an example such as (246a) to report on Els' activities during the past-tense interval evoked by the adverbial phrase vorige week'last week'. This utterance can be followed in discourse by the utterances in (246b-d), which subdivide this past-tense interval into smaller subparts in a fashion completely parallel to the way in which the present-tense examples in (230b-d) subdivide the present-tense interval evoked by the adverbial phrase deze week'this week' in (230a).

| a. | Els werkte | vorige week | aan de paragraaf | over het temporele systeem. | past | |

| Els worked | last week | on the section | about the tense system | |||

| 'Last week, Els was working on the section on the tense system.' | ||||||

| b. | Op maandag | had | ze | de algemene opbouw | vastgesteld. | past perfect | |

| on Monday | had | she | the overall organization | prt.-determined | |||

| 'On Monday, she had determined the overall organization.' | |||||||

| c. | Op dinsdag | schreef | ze | de inleiding. | simple past | |

| on Tuesday | wrote | she | the introduction | |||

| 'On Tuesday, she wrote the introduction.' | ||||||

| d. | Daarna | zou | ze | de acht temporele vormen | beschrijven. | future in past | |

| after.that | would | she | the eight tense forms | describe | |||

| 'After that, she would describe the eight tense forms.' | |||||||

| e. | Ze | zou | het | zaterdag | wel | voltooid | hebben. | future perfect in past | |

| she | would | it | Saturday | prt | completed | have | |||

| 'She probably would have finished it on Saturday.' | |||||||||

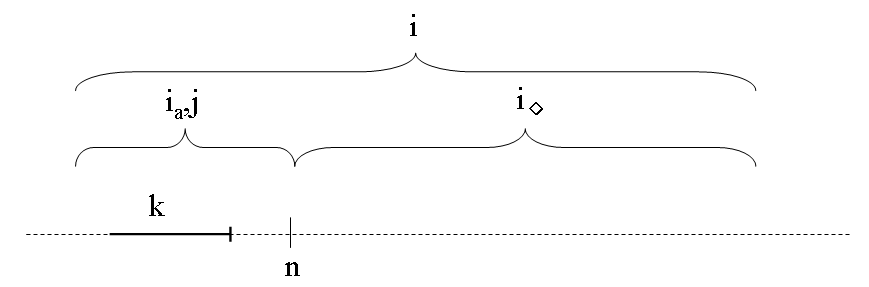

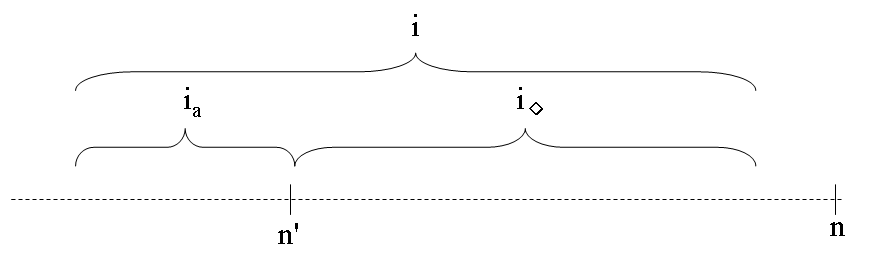

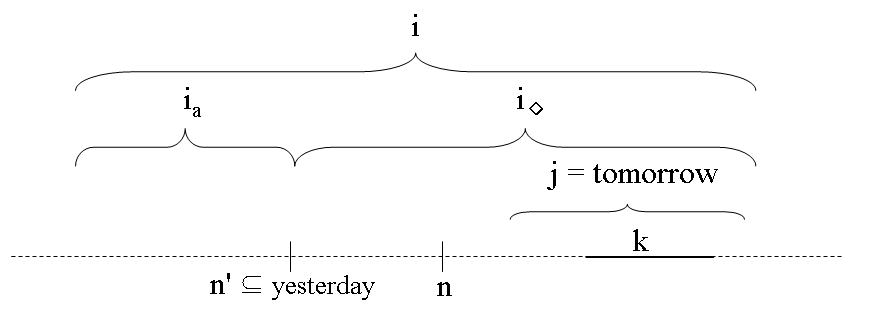

The striking parallelism between the four present-tense forms and the four past-tense forms makes it possible to assume that the mental representations of the past tenses are similar to the ones for the present tenses except for n. To account for the striking parallelism between the four present tenses and the four past tenses, we will assume that the past tenses are defined by means of a virtual "speech-time-in-the past", which we will refer to as n'. To make this a bit more concrete, assume that the speaker of the discourse chunk in (246) is telling about a conversation he has had with Els. We may then identify n' with the moment that the conversation took place; the speaker is repeating the information provided by Els from the perspective of that specific point in time. This leads to the representation in Figure 12, in which the dotted line represents the time line, index i stands for the time interval that is construed as the past (that is, the then-present) for the speaker/hearer, ia for the actualized part of the past at n', and i◊for the non-actualized part of the past at n'.

In what follows we will show that the four past tenses in Table 9 differ with respect to the way in which they locate the eventuality k in past-tense interval i. Before we start doing this, we want to point out that the present proposal diverges in one crucial respect from the proposal in Verkuyl (2008). In Figure 12, we placed speech time n external to i and Verkuyl indeed claims that this is a defining property of the past-tense interval i, as is clear from his definition of present and past tense given in Subsection A, which is repeated here as (247).

| a. | Present: i ○ n | i includes speech time n |

| b. | Past: i < n | i precedes speech time n |

The idea that the past-tense interval must precede speech time n does not seem to follow from anything in the system. There is, for example, no a priori reason for rejecting the idea that, like the present-tense interval, the past-tense interval can be stretched indefinitely, and is thus able to include speech time n. In the subsections below, we will in fact provide empirical evidence that inclusion of n is possible. For example, the future in the past and future perfect in the past examples in (248) show that eventuality k can readily be placed after speech time n.

| a. | Marie zou | morgen | vertrekken. | |

| Marie would | tomorrow | leave | ||

| 'Marie would leave tomorrow.' | ||||

| b. | Marie zou | oma | morgen | bezocht | hebben. | |

| Marie would | grandma | tomorrow | visited | have | ||

| 'Marie would have visited Grandma tomorrow.' | ||||||

In order to formally account for the acceptability of examples such as (248), Broekhuis & Verkuyl (2014) adapted the definition in (247b) as in (249b). Note that the examples in (248) also have a modal meaning component; we will ignore this for the moment but return to it in Section 1.5.2.

| a. | Present: i ○ n | i includes speech time n |

| b. | Past: i ○ n' | i includes virtual speech-time-in-the-past n' |

The definitions in (249) leave the core of the binary tense system unaffected given that they maintain the asymmetry between the present and the past but now on the basis of an opposition between the now-present (characterized by the inclusion of n) and the then-present (characterized by the inclusion of n'). The now-present could be seen as the time interval that is immediately accessible to and directly relevant for the speaker/hearer-in-the-present, whereas the then-present should rather be seen as the time interval accessible to and relevant for some speaker/hearer-in-the-past; see Janssen (1983:324ff.) and Boogaart & Janssen (2007) for a review of a number of descriptions in cognitive terms of the distinction between past and present that may prove useful for sharpening the characterization of the now- and then-present proposed here. The definition of past in (249b) is also preferred to the one in (247b) for theoretical reasons: first, it formally accounts for the parallel architecture of the present and the past and, second, it solves the problem that n' did not play an explicit role in the definition of the three binary oppositions given in Subsection A, and was therefore left undefined.

The following subsections will show that the four past tenses in Table 9 in the introduction to this subsection differ with respect to (i) the location of eventuality k denoted by the lexical projection of the main verb within present-tense interval i, and (ii) whether or not it is presented as completed within its own past-tense interval j. Recall that we will focus on the temporal interpretations cross-linguistically attributed to the tenses in Table 9 and postpone the discussion of the more special temporal and the non-temporal aspects of their interpretations in Dutch to Section 1.5.4.

The simple past expresses that eventuality k takes place during past-tense interval i. This can be expressed by means of Figure 13, in which the continuous line below k refers to the time interval during which the eventuality holds. The continuous line below k indicates that the default reading of an example such as Ik wandelde'I was walking' is that eventuality k takes place at n'.

By stating that j = i, Figure 13 also expresses that the simple past does not have any implications for the time preceding or following the relevant past-tense interval i: the eventuality k may or may not hold before/after i. Thus, an example such as (250) does not say anything about the speaker's feelings on the day before yesterday or today. This also implies that the simple past cannot shed any light on the issue of whether speech time n can be included in past-tense interval i.

| Ik | was | gisteren | erg gelukkig. | ||

| I | was | yesterday | very happy | ||

| 'I was very happy yesterday.' | |||||

The default reading of the past perfect is that eventuality k takes place before n', that is, k is located in the actualized past-tense interval ia (j = ia). In addition, the past perfect presents the eventuality as a discrete, bounded unit that is completed within time interval j, that is, cannot be continued after n'; this is again represented by means of the short vertical line after the continuous line below k. Given that k precedes n' and n' precedes n, k also precedes n, which implies that examples of this type cannot shed any light on whether speech time n can be included in the past-tense interval i.

The future in the past expresses that the eventuality k takes place after n', that is, k is located in the non-actualized part of the past-tense interval (j = i◊).

The future in the past examples in (251b&c) show that speech time n can be included in the past-tense interval. We have already seen above that this refutes the definition of past in (247b) and supports the revised definition in (249b).

| a. | Els zou | gisteren | wandelen. | |

| Els would | yesterday | walk |

| b. | Els zou | vandaag | wandelen. | |

| Els would | today | walk |

| c. | Els zou | morgen | wandelen. | |

| Els would | tomorrow | walk |

The interpretation of the future perfect in the past is similar to that of the future in the past, but requires the state of affairs to be completed within time span i◊.

The difference between the future in the past and the future perfect in the past is parallel to the difference between the future and the future perfect discussed in Subsection A: in future in the past examples such as (252a) the focus is on the progression of the eventuality, which is placed in its entirety after n', whereas in future perfect in the past examples such as (252b) the focus is on the completion of the eventuality and no particular claim is made concerning the starting point of the event.

| a. | Het ijs | zou | gisteren | smelten. | |

| the ice | would | yesterday | melt | ||

| 'The ice would melt yesterday.' | |||||

| b. | Het ijs | zou | gisteren | gesmolten | zijn. | |

| the ice | will | yesterday | melted | be | ||

| 'The ice would have melted yesterday.' | ||||||

Similar examples with the achievement die brief schrijven are given in (253): the future in the past in (253a) locates the entire eventuality after n', whereas the future perfect in the past in (253b) does not seem to make any claim about the starting point of the eventuality but simply expresses that the eventuality will be completed after n' (but within i◊).

| a. | Jan zou | gisteren | die brief | schrijven. | |

| Jan would | yesterday | that letter | write | ||

| 'Jan would write that letter yesterday.' | |||||

| b. | Jan zou | gisteren | die brief | geschreven | hebben. | |

| Jan would | yesterday | that letter | written | have | ||

| 'Jan would have written that letter yesterday.' | ||||||

The examples in (254) with the adverbial phrase morgen'tomorrow' show that the future perfect in the past provides evidence in favor of the claim that speech time n can be included in the past-tense interval. We have already seen that this refutes the definition of past in (247b) and supports the revised definition in (249b).

| a. | Het ijs | zou | morgen | gesmolten | zijn. | |

| the ice | will | tomorrow | melted | be | ||

| 'The ice would have melted tonight.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan zou | morgen | die brief | geschreven | hebben. | |

| Jan would | tomorrow | that letter | written | have | ||

| 'Jan would have written a letter tomorrow.' | ||||||

So far, we have discussed the three binary features in (255) assumed within Te Winkel/Verkuyl's binary tense theory: these features define four present and four past tenses, which were exemplified in Table 9.

| a. | ±past: present versus past |

| b. | ±posterior: future versus non-future |

| c. | ±perfect: imperfect versus perfect |

Subsections A and C discussed the default interpretations assigned to these present and past tenses by Verkuyl (2008). We also discussed Verkuyl's formalizations of the features in (255) and saw that there was reason to somewhat adapt the definition of +past. This resulted in the set of definitions in (256).

| a. | Present: i ○ n | i includes speech time n |

| a'. | Past: i ○ n' | i includes virtual speech-time-in-the-past n' |

| b. | Non-future: i ≈ j | i and j synchronize |

| b'. | Future: ia < j | ia precedes j |

| c. | Imperfect: k ≼ j | k need not be completed within j |

| c'. | Perfect: k ≺ j | k is completed within j |

An important finding of the previous subsections is that in principle the present and past interval can be indefinite, with the result that the past-tense interval may include speech time n. This means that the present and the past do not refer to mutually exclusive temporal domains and, consequently, that it should be possible to discuss eventualities both as part of the past and as part of the present domain. This subsection provides evidence in favor of this position and will argue that the choice between the two options is a matter of perspective, that is, whether the eventuality is viewed from the perspective of speech time n or the virtual speech time in the past n'.

The use of adverbial phrases of time in sentences with a past tense may introduce a so-called supratemporal ambiguity; cf. Verkuyl (2008:118-123). This ambiguity is especially visible when the adverbial phrase occupies the first position of the sentence, as in (257).

| a. | Om vijf uur | ging | Marie weg. | |

| at 5 oʼclock | went | Marie away | ||

| 'Marie would leave at 5 oʼclock.' | ||||

| b. | Een uur geleden | had Marie nog | zwart haar. | |

| an hour ago | had Marie still | black hair | ||

| 'An hour ago Marie still had black hair.' | ||||

The two sentences in (257) have a run-of-the-mill "real event" interpretation in the sense that the sentence is about Marie's departure or about Marie having black hair at the time indicated by the adverbial phrase; in such cases the adverbial phrase functions as a regular temporal modifier of the time interval j that includes eventuality k. There is, however, also a supratemporal interpretation in which the eventuality itself does not play any particular role apart from being the topic of discussion. On this interpretation, the speaker of (257a) expresses that his most recent information about Marie's departure goes back to five o'clock. This means that the adverbial phrase om vijf uur'at five oʼclock' thus does not pertain to the location of the eventuality on the time axis but to the speaker: "according to my information at five oclock, the situation was such that Marie would be leaving". In a similar way, (257b) may be interpreted as a correction of a mistake signaled by the speaker in, e.g., a manuscript; the sentence is not about the character Marie but about information about the character Marie: "An hour ago, I read that Marie is black-haired (but now it is mentioned that Jan is fond of her auburn hair)".

Past-tense clauses are compatible with future eventualities on a supratemporal reading. Consider a situation in which the speaker is discussing Els' plans for some time interval after speech time n. He may then compare the information available at two different moments in time: sentence (258a), for example, compares the information that the speaker had yesterday with the information that he has just received. The first conjunct of (258a) also illustrates that past-tense clauses with a supratemporal reading are compatible with locating the eventuality k after speech time; the speaker's talk is located in the speaker's future. Example (258b) in fact shows that it is even possible to make the future location of k explicit by means of a second adverbial phrase like morgen'tomorrow', particularly when adding the particle nog right behind gisteren'yesterday'; see Boogaart & Janssen (2007) for similar examples.

| a. | Gisteren | zou | Els mijn lezing | bijwonen, | maar | nu | gaat ze op vakantie. | |

| yesterday | would | Els my talk | attend | but | now | goes she on holiday | ||

| 'As of yesterday, the plan was that Els would attend my lecture but now I have information that sheʼll be going on holiday.' | ||||||||

| b. | Gisteren (nog) | zou | Els morgen | mijn lezing | bijwonen, | maar | nu | gaat | ze | op vakantie. | ||

| yesterday prt | would | Els tomorrow | my lecture | attend | but | now | goes | she | on holiday | |||

| 'As of yesterday, the plan was that Els would attend my talk tomorrow but now I have information that sheʼll be going on holiday.' | ||||||||||||

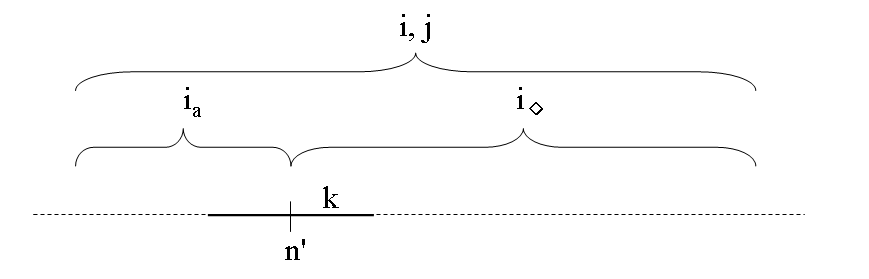

That the past tense in the first conjunct of the examples in (258) is compatible with locating the eventuality after speech time n and that the adverbs gisteren'yesterday' and morgen'tomorrow' can be used in a single clause is exceptional. However, that this is possible need not surprise us when we realize that speech time n can be included in the past-tense interval. As is illustrated in Figure 17 for example (258b), the first conjuncts in sentences such as (258) give rise to completely coherent interpretations. The notation used aims at expressing that the adverbial phrase gisteren is a supra-temporal modifier of the virtual speech-time-in-the past n', whereas the adverbial phrase morgen'tomorrow' functions as a regular temporal modifier of j.

The claim that speech time n may be included in the past-tense interval also has important consequences for the description of the so-called sequence of tense phenomenon, that is, the fact that the tense of a dependent clause can be adapted to concord with the past tense of the matrix clause. Sequence of tense is illustrated by means of the two examples in (259): example (259a) is unacceptable if we interpret the adverb morgen'tomorrow' as a temporal modifier of the eventuality k, whereas example (259b) is fully acceptable in that case.

| a. | $ | Jan vertrok | morgen. |

| Jan left | tomorrow | ||

| 'Jan was leaving tomorrow.' | |||

| b. | Els zei | [dat | Jan morgen | vertrok]. | |

| Els said | that | Jan tomorrow | left | ||

| 'Els said that Jan was leaving tomorrow.' | |||||

The unacceptability of (259a) is normally taken to represent the normal case: past tense is incompatible with adverbial phrases like morgen that situate the eventuality after speech time n, and therefore (259a) cannot be interpreted as a modifier of the then-present j of the eventuality k; on this view, the sequence-of-tense example in (259b) is unexpected and must therefore considered to be a special case. If we assume that speech time n can be included in the past-tense interval, on he other hand, the acceptability of (259b) is expected without further ado; the eventualities in the main and the embedded clause are both viewed as belonging to past-tense interval i, which happens to also contain speech time n. The real problem on this view is the unacceptability of example (259a) given that the system predicts this example to be possible in the intended reading as well.

The claim that the past-tense interval may include speech time n may also account for the contrast between the two examples in (260). In (260a) the eventualities are both considered to be part of the past-tense interval, and as a result of this we cannot determine from this example whether the speaker believes that Els is still pregnant at speech time n; this may or may not be the case. In (260b), on the other hand, the eventuality of Els being pregnant is presented as being part of the present time domain, and the speaker therefore does imply that Els is still expecting at speech time n; see Hornstein (1990: Section 4.1) for similar intuitions.

| a. | Jan zei | [dat | Els zwanger | was]. | |

| Jan said | that | Els pregnant | was | ||

| 'Jan said that Els was pregnant.' | |||||

| b. | Jan | zei | [dat | Els zwanger | is]. | |

| Jan | said | that | Els pregnant | is | ||

| 'Jan said that Els is pregnant.' | ||||||

This contrast in interpretation can also be demonstrated by means of the examples in (261). Because sequence-of-tense constructions do not imply that the eventuality expressed by the embedded clause still endures at speech time n, the continuation in (261a) is fully natural; it is suggested that Marie has given birth and hence is a mother by now. In (261b), on the other hand, the continuation gives rise to a semantic anomaly given that the use of the present in the embedded clause strongly suggests that the speaker believes that Marie is still pregnant.

| a. | Jan zei | [dat | Els zwanger | was]; | ze | zal | ondertussen | wel | moeder | zijn. | |

| Jan said | that | Els pregnant | was | she | will | by.now | prt | mother | be | ||

| 'Jan said that Els was pregnant; sheʼll probably be a mother by now.' | |||||||||||

| b. | $ | Jan | zei | [dat | Els zwanger | is]; | ze | zal | ondertussen | wel | moeder | zijn. |

| Jan | said | that | Els pregnant | is | she | will | by.now | prt | mother | be | ||

| 'Jan said that Els is pregnant; sheʼll probably be a mother by now.' | ||||||||||||

A similar account can be given for the observation in Kiparsky & Kiparsky (1970:162-3), which is illustrated in (262), that for some speakers factive and non-factive constructions differ in that the former normally have optional sequence of tense, whereas the latter (often) have obligatory sequence of tense. The reason for this is again that the use of the present tense suggests that the speaker believes that the eventuality expressed by the embedded clause holds at speech time n. We used a percentage sign in (262b) to indicate that some speakers at least marginally accept the use of the present tense in non-factive constructions like this.

| a. | De oude Grieken | wisten | al | [dat | de wereld | rond | was/is]. | |

| the old Greeks | knew | already | that | the world | round | was/is | ||

| 'The old Greeks knew already that the world is round.' | ||||||||

| b. | De kerk | beweerde | lang | [dat | de wereld | plat | was/%is]. | |

| the church | claimed | long | that | the world | flat | was/is | ||

| 'The church claimed for a long time that the World was flat.' | ||||||||

The discussion in the previous subsection has shown that the claim that the past-tense interval may include speech time n correctly predicts that sequence of tense is not required, and may even be impossible if the right conditions are met. As we noticed earlier in our discussion of the examples in (259), this in a sense reverses the traditional problem; it is not the sequence-of-tense example in (259b) that constitutes a problem but the fact that in simple clauses such as (259a), the past tense blocks the use of adverbial phrases like morgen'tomorrow' that locate the eventuality after speech time n.

It should be noted, however, that under specific conditions past tense actually can be combined with adverbs like morgen. This holds, for instance, for the question in (263b), provided by Angeliek van Hout (p.c.). The two examples in (263) differ in their point of perspective: (263a) expresses that speaker assumes on the basis of his knowledge at speech time n that the addressee will come tomorrow, whereas (263b) expresses that the speaker assumes this on the basis of his knowledge at virtual speech-time-in-the-past n'. Some speakers report that (263b) feels somewhat more polite than (263a), which may be related to this difference in perspective; by using (263b), the speaker explicitly leaves open the possibility that his information is outdated, and, consequently, that the conclusion that he draws from this information is wrong.

| a. | Je | komt | morgen | toch? | |

| you | come | tomorrow | prt | ||

| 'You have the intention to come tomorrow, donʼt you?' | |||||

| b. | Je | kwam | morgen | toch? | |

| you | came | tomorrow | prt | ||

| 'You had the intention to come tomorrow, didnʼt you?' | |||||

Past tenses can also be combined with the adverb morgen in questions such as (264b). The difference again involves a difference in perspective. By using question (264a), the speaker is simply inquiring after some information available at n; he has the expectation that there will be a visitor tomorrow and he wants to know who that visitor is. Example (264b) is used when the speaker is aware of the fact that he had information about the identity of the visitor at some virtual speech-time-in-the-past n', but does not remember that information (which is typically signaled by the string ook al weer).

| a. | Wie komt er morgen? | |

| who comes there tomorrow | ||

| 'Who is coming tomorrow?' |

| b. | Wie | kwam | morgen | ook al weer? | |

| who | came | tomorrow | ook al weer | ||

| 'Please, tell me again who will come tomorrow?' | |||||

Yet another example, taken from Boogaart & Janssen (2007: 809), is given in (265). Example (265a) simply states the speaker's intention to leave tomorrow, whereas example (265b) leaves open the possibility that there are reasons that were not known at some virtual speech-time-in-the-past n' that may forestall the implementation of the speaker's intention to leave.

| a. | Ik vertrek | morgen. | |

| I leave | tomorrow | ||

| 'Iʼll leave tomorrow.' | |||

| b. | Ik | vertrok | morgen | graag. | |

| I | left | tomorrow | gladly | ||

| 'Iʼdʼve liked to leave tomorrow.' | |||||

A final example that seems closely related to the one in (265b) and which is also taken in a slightly adapted from Boogaart & Janssen is given in (266b). Examples like that can be used as objections to some order/request by showing that it is inconsistent with some earlier obligation or plan.

| a. | Je | moet | morgen | thuis | blijven. | |

| you | have.to | tomorrow | at.home | stay | ||

| 'You have to stay at home tomorrow.' | ||||||

| b. | Maar | ik | vertrok | morgen | naar Budapest! | |

| but | I | left | tomorrow | to Budapest | ||

| 'But I was supposed to leave for Budapest tomorrow.' | ||||||

The examples in (263) to (266) show that there is no inherent prohibition on combining past tenses with adverbs like morgen'tomorrow', and thus show that there is no need to build such a prohibition into tense theory. Of course, this still leaves us with the unacceptability of simple declarative clauses like Jan kwam morgen'Jan came tomorrow', but Section 1.5.4 will solve this problem by arguing that this example is excluded not because it is semantically incoherent but for pragmatic reasons: Grice's maxim of quantity prefers the use of the simple present/future in cases like this.

The previous subsection has shown that it is possible to combine past tenses with adverbs referring to time intervals following speech time n. Similarly, it seems possible to combine present tenses with adverbs like gisteren'yesterday' that refer to time intervals preceding speech time n, subsection A2 has already discussed this for present perfect constructions such as (267) and has shown that this is fully allowed by our definitions in (256); since neither the definition of present in (256a) nor the definition of perfect in (256c) imposes any restriction on the location of j (or k) with respect to n, the adverbial gisteren'yesterday' may be analyzed as an identifier of jon the assumption that the time interval referred to by gisteren is part of a larger present-tense interval i that includes speech time n.

| a. | Ik | heb | gisteren | gewandeld. | |

| I | have | yesterday | walked | ||

| 'I walked yesterday.' | |||||

In fact, we would expect for the same reason that it is also possible to combine adverbs like gisteren with the simple present: the definition of present in (256a) does not impose any restriction on the location of j (or k) with respect to n. This means that we expect examples such as (268c) to be possible alongside (268a&b). Although the examples in (268a&b) are certainly more frequent, examples such as (268c) occur frequently in speech and can readily be found on the internet.

| a. | Ik | las | gisteren/daarnet | in de krant | dat ... | |

| I | readpast | yesterday/just.now | in the newspaper | that | ||

| 'Yesterday/A moment ago, I read in the newspaper that ...' | ||||||

| b. | Ik | heb | gisteren/daarnet | in de krant | gelezen | dat ... | |

| I | have | yesterday/just.now | in the newspaper | readpart | that | ||

| 'Yesterday/A moment ago, I read in the newspaper that ...' | |||||||

| c. | Ik | lees | gisteren/daarnet | in de krant | dat ... | |

| I | readpresent | yesterday/just.now | in the newspaper | that | ||

| 'Yesterday/A moment ago, I was reading in the newspaper that ...' | ||||||

The acceptability of examples such as (268c) need not surprise us and in fact need no special stipulation. The only thing we have to account for is why the frequency of such examples is relatively low: one reason that may come to mind is simply that examples of this type are blocked by the perfect-tense example in (268b) because the latter is more precise in that it presents the eventuality as completed.

Present-tense examples such as (268c) are especially common in narrative contexts as an alternative for the simple past, for which reason this use of the simple present is often referred to as the historical present. The historical present is often said to result in a more vivid narrative style (see Haeseryn et al. 1997:120), which can be readily understood from the perspective of binary tense theory. First, it should be noted that the simple past is normally preferred in narrative contexts over the present perfect given that it presents the story not as a series of completed eventualities but as a series of ongoing events. However, since the simple past presents the story from the perspective of some virtual speech-time-in-the-past, it maintains a certain distance between the events discussed and the listener/reader. The vividness of the historical present is the result of the fact that the simple present removes this distance by presenting the story as part of the actual present-tense interval of the listener/reader.

The historical present has become convention that is frequently used in the narration of historical events, even if the events are more likely construed as being part of some past-tense interval; see (269). Again, the goal of using the historical present is to bridge the gap between the narrated events and the reader by presenting these events as part of the reader's present-tense interval.

| a. | In 1957 verscheen | Syntactic structures, | dat Chomsky beroemd zou maken. | |

| in 1957 appeared | Syntactic structures | that Chomsky famous would make | ||

| 'In 1957, Syntactic Structures appeared, which would make Chomsky famous.' | ||||

| b. | In 1957 | verschijnt | Syntactic structures, | dat | Chomsky beroemd | zal maken. | |

| in 1957 | appears | Syntactic structures | that | Chomsky famous | will make | ||

| 'In 1957, Syntactic Structures appears, which will make Chomsky famous.' | |||||||

This use of the historical present is therefore not very special from a grammatical point of view given that it just involves the pretense that n' = n, and we will therefore not digress any further on this use. The conclusion that we can draw from the discussion above is that the stylistic effect of the so-called historical present confirms our main claim that the choice between past and present tense is a matter of perspective.

This subsection concludes our discussion of the choice between present and past by showing that tense determines not only the perspective on the eventuality expressed by the lexical projection of the main verb but also affects the interpretation of so-called non-rigid designators like de minister-president'the prime minister'; cf. Cremers (1980) and Janssen (1983). Non-rigid designators are noun phrases that do not have a fixed referent but referents that change over time; whereas the noun phrase de minister-president refers to Wim Kok in the period August 1994–July 2002, it refers to Jan Peter Balkenende in the period July 2002–February 2010.

That choice of tense may affect the interpretation of the noun phrase can be illustrated by means of the examples in (270). The interpretation of the present-tense example in (270a) depends on the actual speech time n; if uttered in 1996, it is an assertion about Wim Kok, if uttered in 2008, it is an assertion about Jan Peter Balkenende. Similarly, the interpretation of the past-tense example in (270b) depends on the location of the virtual speech-time-in-the past n': in a discussion about the period 1994 to 2002, it will be interpreted as an assertion about Wim Kok, but in a discussion about the period 2002 to 2010, as an assertion about Jan Peter Balkenende. Crucially, example (270b) need not be construed as an assertion about the person who performs the function of prime minister at speech time n.

| a. | De minister-president | is een bekwaam bestuurder. | |

| the prime.minister | is an able governor |

| b. | De minister-president | was een bekwaam bestuurder. | |

| the prime.minister | was an able governor |

The examples in (270) show that present/past tense fixes the reference of non-rigid designators; we select their reference at n/n'. Now, consider the examples in (271), in which the index now on the noun phrase is used to indicate that the intended referent is the one who performs the function of prime minister at speech time n. The number sign indicates that example (271a) is not very felicitous when one wants to express that the current prime minister had attended high school when he was young. This follows immediately from the claim that the reference of non-rigid designators is determined by tense; the past tense indicates that the description de minister-president can only refer to the person performing the function of prime minister at virtual speech-time-in-the-past n'. Example (271b), on the other hand, can felicitously express the intended meaning given that it simply presents the prime minister's school days as part of the present-tense interval: the person referred to by the description de minister-president at speech time n is said to have attended high school during the actualized part of the present-tense interval.

| a. | # | De minister-president | zat | op het gymnasium. |

| the prime.ministernow | sat | on the high.school | ||

| 'The prime minister attended high school.' | ||||

| b. | De minister-president | heeft | op het gymnasium | gezeten. | |

| the prime.ministernow | has | on the high.school | sat | ||

| 'The prime minister has attended high school.' | |||||

For completeness' sake, note that we do not claim that it is impossible to interpret a non-rigid designator from the perspective of speech time n in past tense sentences, but this is possible only if the description happens to refer to the same individual at n and n'. This is illustrated by the fact that the two examples in (272) are both perfectly acceptable.

| a. | De minister-president | was | enkele dagen | in Brussel. | |

| the prime.ministernow | was | some days | in Brussels | ||

| 'The prime minister was in Brussels for a couple of days.' | |||||

| b. | De minister-president | is enkele dagen | in Brussel | geweest. | |

| the prime.ministernow | is some days | in Brussels | been | ||

| 'The prime minister has been in Brussels for a couple of days.' | |||||

The discussion above has shown that present/past tense not only determines the perspective from which the eventuality as a whole is observed, but also affects the interpretation of noun phrases that function as non-rigid designators.

Before closing this subsection, we want to mention that Cremers (1980:44) has claimed that the judgments on the examples above only hold if a non-rigid designators is used descriptively; he suggests that in certain contexts, such noun phrases can also be used as proper names. An example such as (273b), for example, can readily be used in a historical narrative to refer to Queen Wilhelmina or Queen Juliana, even if the story is told/written during the regency of Queen Beatrix.

| a. | De koningin | was zich | voortdurend | bewust | van ... | |

| the queenpast | was refl | continuously | aware | of | ||

| 'The Queen was continuously aware of ....' | ||||||

| b. | De koningin | is zich | voortdurend | bewust | van ... | |

| the queenpast | is refl | continuously | aware | of | ||

| 'The Queen is constantly aware of ...' | ||||||

Since the previous subsection has already mentioned that historical narratives often use the historical present, an alternative approach to account for the interpretation in (273b) might be that it is this use of the present that affects the interpretation of non-rigid designators; the pretense that n' = n simply does not block the option of interpreting the non-rigid designator with respect to n'. We leave this issue for future research.