- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

Normally, wh-movement is semantically or functionally motivated, which is especially clear in the case of wh-questions and topicalization constructions: Wh-movement in question (465a) is needed to create the operator-variable configuration in (465a'), while topicalization in example (465b) results in a special information-structural configuration, such as the topic-comment structure in (465b'). The traces indicated by t in the primeless examples in (465) are traditionally motivated by the fact that the displaced elements wat'what' and dit boek'this book' also perform the syntactic function of direct object; they indicate the designated argument position that is assigned the thematic role of theme as well as accusative case by the transitive main verb kopen'to buy'.

| a. | Wati | heeft | Peter ti | gekocht? | |

| what | has | Peter | bought | ||

| 'What has Peter bought?' | |||||

| a'. | ?x (Peter has bought x) |

| b. | Dit boeki | heeft | Peter ti | gekocht. | |

| this book | has | Peter | bought | ||

| 'This book, Peter has bought.' | |||||

| b'. | [topic Dit boek] [comment heeft Peter gekocht]. |

Of course, there are theories in which thematic roles and/or case are assigned in the surface position of the wh -phrase but there are empirical reasons for assuming that these elements are semantically interpreted in the position of their trace, a phenomenon that has become known as reconstruction; we refer the reader to Subsection IIB for the origin of this technical notion. This section will mainly illustrate reconstruction effects by means of the binding properties of wh -moved elements; see Barrs (2001) for a similar review for English, subsection I will therefore start by providing some theoretical background on binding. Given that reconstruction facts are easiest to demonstrate by means of topicalization, Subsection II will start with a discussion of this structure; reconstruction in questions and relative clauses is discussed in, respectively, III and IV. As the discussion of topicalization, w h -movement and relativization suffices to sketch a general picture of the issues involved, we will not discuss reconstruction in wh -exclamative and comparative (sub)deletion constructions (which have in fact not played a major role in the descriptive and theoretical literature on the phenomenon so far).

Most research on binding is based on the empirical observation that referential personal pronouns such as hem'him' and (complex) reflexive personal pronouns such as zichzelf'himself' are in complementary distribution; this is illustrated for Dutch in the primeless examples in (466), in which coreferentiality is indicated by italics. The primed examples show that referential non-pronominal noun phrases normally cannot be used if a referential or a reflexive personal pronoun is possible; these examples are excluded on the reading that Jan and de jongen refer to the same individual.

| a. | Ik | denk | [dat | Jan | zichzelf/*hem | bewondert]. | |

| I | think | that | Jan | himself/*him | admires | ||

| 'I think that Jan admires himself.' | |||||||

| a'. | * | Ik | denk | [dat | Jan | de jongen | bewondert]. |

| I | think | that | Jan | the boy | admires |

| b. | Jan denkt | [dat | ik | hem/*zichzelf | bewonder]. | |

| Jan thinks | that | I | him/himself | admire | ||

| 'Jan thinks that I admire him.' | ||||||

| b'. | * | Jan denkt | [dat | ik | de jongen | bewonder]. |

| Jan thinks | that | I | the boy | admire |

Data like (466) are accounted for by binding theory, which has found its classic formulation in the so-called binding conditions proposed in Chomsky (1981), which we provide in a somewhat loose formulation as (467).

| a. | Reflexive and reciprocal personal pronouns are bound in their local domain. |

| b. | Referential personal pronouns are free (= not bound) in their local domain. |

| c. | Referential noun phrases like Jan or de jongen'the boy' are free. |

These conditions are extensively discussed in Section N5.2.1.5, but we will repeat some core issues here that are needed for our present purposes. A noun phrase is said to be bound if it is coreferential with a c-commanding antecedent. The term c-command refers to an asymmetric syntactic relation between the constituents in a sentence, which can be made more precise by means of the hierarchy in (468), in which A > B indicates that A c-commands B and everything that is embedded in B.

| C-command hierarchy: | ||

| subject > direct object > indirect object-PP > PP-complement > adjunct |

We can thus say that, under the intended coreferential readings, the direct objects in the (a)-examples in (466) are bound by the subject noun phrase Jan of the embedded clause, and that the embedded nominal direct objects in the (b)-examples are bound by the subject noun phrase Jan of the main clause; recall that A > B in (468) indicates that A c-commands B and everything that is embedded in B. Now consider again the three binding conditions in (467), which are normally referred to as conditions A, B and C. The fact that the primed examples in (466) are ungrammatical on the intended readings shows that c-command does not suffice to license binding: binding condition C expresses this by saying that a referential non-pronominal noun phrase cannot have a c-commanding antecedent at all. Binding conditions A and B further express that reflexive/reciprocal and referential personal pronouns differ with respect to the syntactic domain in which binding is possible, that is, in which they must/can have a c-commanding antecedent. If we assume for the moment that the relevant domain is the minimal clause in which we find the bound element, the data in (466a&b) follow: in (466a) the antecedent Jan is within the local domain of the pronoun, and binding conditions A and B predict that a reflexive pronoun can, but a referential pronoun cannot be bound by Jan; in (466b) the antecedent Jan is not within the local domain of the pronoun, and binding conditions A and B predict that a referential pronoun can, but a reflexive pronoun cannot be bound by Jan. This derives the complementary distribution of the referential and reflexive personal pronouns illustrated in (466a&b).

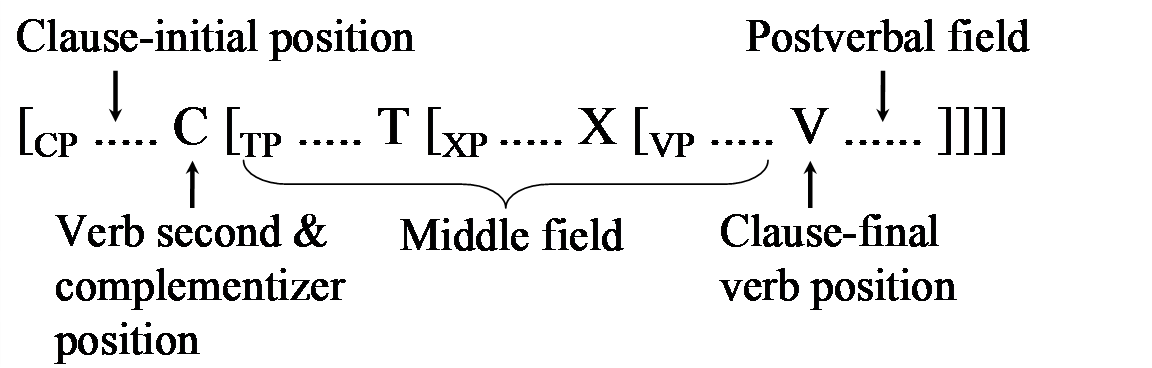

The crucial thing for our discussion of reconstruction is that it is normally assumed that the c-command hierarchy in (468) is not a primitive notion, but derived from the hierarchical structural relations between the elements mentioned in it. It suffices for our present purpose to say that the subject of a clause c-commands the direct object of the same clause because the former is in a structurally higher position than the latter; in the overall structure of the clause given in (469), which is extensively discussed in Chapter 9, the subject occupies the specifier position of TP immediately following the C-position, while the object occupies some lower position within XP.

|

If c-command should indeed be defined in terms of structural representations, wh-movement affects the c-command relations between the clausal constituents: after wh-movement of the object into the specifier of CP, the object will c-command the subject in the specifier of TP. We therefore expect wh-movement to alter the binding possibilities, but the following subsections will show that this expectation is not borne out; the wh-moved phrase normally behaves as if it still occupies its original position.

That wh-movement does not affect binding relations can be easily demonstrated by means of topicalization. We will start with a presentation of the core data, which shows that the binding possibilities are computed from the original position of the topicalized phrase. After this, we will briefly compare reconstruction effects with so-called connectivity effects found in contrastive left-dislocation constructions.

If the binding conditions were calculated from the landing site of wh-movement, topicalization of a reflexive pronominal direct object is expected to bleed binding. Example (470b) shows, however, that with respect to binding the topicalized reflexive pronoun zichzelf behaves as if it is still in the position indicated by its trace; coreferentiality is again indicated by italics.

| a. | Jan | bewondert | zichzelf het meest. | |

| Jan | admires | himself the most | ||

| 'Jan admires himself the most.' | ||||

| b. | Zichzelfi | bewondert | Jan ti | het meest. | |

| himself | admires | Jan | the most | ||

| 'Himself Jan admires the most.' | |||||

That topicalization does not bleed binding can also be illustrated by means of the examples in (471), in which a reciprocal possessive pronoun is embedded in a direct object; topicalization of this object does not affect the binding possibilities. Note in passing that, contrary to reciprocal and referential personal pronouns, reciprocal and referential possessive pronouns are not in complementary distribution given that elkaars can readily be replaced by hun'their'; we refer the reader to Section N5.2.2 for detailed discussion.

| a. | Zij | bewonderen | [elkaars moeder] | het meest. | |

| they | admire | each.otherʼs mother | the most | ||

| 'They admire each otherʼs mother the most.' | |||||

| b. | [Elkaars moeder]i | bewonderen | zij ti | het meest. | |

| each.otherʼs mother | admire | they | the most | ||

| 'Each otherʼs mother they admire the most.' | |||||

Another case showing that topicalization does not bleed binding is illustrated by the examples in (472), which allow a bound-variable reading of the possessive pronoun zijn'his'; according to this reading every person x admires his own parents: ∀x (x:person) admire (x, x's parents). This reading only arises if the quantifier binds (hence: c-commands) a referential pronoun and we might therefore expect that topicalization in (472b) would make this reading impossible, but this expectation is not borne out.

| a. | Iedereen | bewondert | zijn (eigen) ouders | het meest. | |

| everyone | admires | his own parents | the most | ||

| 'Everyone admires his (own) parents the most.' | |||||

| b. | Zijn (eigen) oudersi | bewondert | iedereen ti | het meest. | |

| his own parents | admires | everyone | the most | ||

| 'His (own) parents everyone admires the most.' | |||||

If the binding conditions were calculated from the landing site of wh-movement, topicalization of a referential (pronominal) direct object is expected to enable it to function as the antecedent of the subject of its clause, but example (473b) shows that this is not the case: with respect to binding the objects hem and die jongen again behave as if they are still in the position indicated by their trace.

| a. | * | Jan | bewondert | hem/die jongen | het meest. |

| Jan | admires | him/that boy | the most |

| b. | * | Hemi/Die jongeni | bewondert | Jan ti | het meest. |

| him/that boy | admires | Jan | the most |

A plausible hypothesis would of course be that example (473b) is unacceptable because the subject Jan is bound by the topicalized phrase and thus violates binding condition C. This hypothesis is, however, refuted by the fact that the matrix subject Jan in (474b) can be coreferential with the topicalized pronoun hem'him': the example is perhaps somewhat marked compared to example (466b) but this seems to be a more general property of long topicalization; see the discussion in Section 11.3.3, sub II. This again leads to the conclusion that wh-movement does not affect binding possibilities.

| a. | Jan denkt | [dat | ik | hem/*die jongen | het meest | bewonder]. | |

| Jan thinks | that | I | him/that boy | the most | admire | ||

| 'Jan thinks that I admire him the most.' | |||||||

| b. | (?) | Hem/*Die jongen | denkt | Jan | [dat | ik ti | het meest | bewonder]. |

| him/that boy | thinks | Jan | that | I | the most | admire | ||

| 'Him Jan thinks that I admire the most.' | ||||||||

Reconstruction is sometimes also illustrated in the literature by means of examples such as (475a), in which a bound nominal phrase is embedded in a complementive.

| a. | Jan is [AP | trots [PP | op zichzelf/*hem/*die jongen]]. | |

| Jan is | proud | of himself/him/that boy |

| b. | [AP | trots [PP | op zichzelf/*hem/*die jongen]] | is Jan niet. | |

| [AP | proud | of himself/him/that boy | is Jan not |

Some linguists do not accept (475b) as a convincing example of reconstruction as they assume that the subject originates as the external argument of the AP: on the assumption that the moved phrase is a full small clause that contains an NP-trace of the subject Jan, this trace serves as an antecedent for the nominal phrase.

| a. | Jani is [AP ti | trots [PP | op zichzelf/*hem/*die jongen]]. | |

| Jan is | proud | of himself/him/that boy |

| b. | [AP ti | trots [PP | op zichzelf/*hem/*die jongen]] j | is Jani tj niet. | |

| [AP ti | proud | of himself/him/that boy | is Jan not |

However, even if the representations in (476) are the correct ones, reconstruction is still needed because it is generally assumed that NP-traces are subject to binding condition A as well: like reflexive pronouns, they must be bound by their antecedent (= the moved phrase) within their local domain.

For VP-topicalization constructions like (477b) more or less the same holds: some linguists who assume that the subject is base-generated in the lexical projection of the verb do not accept it as a convincing example of reconstruction since they assume that the topicalized VP also contains the NP-trace of the subject Jan, which can serve as an antecedent. But even if this is true, reconstruction is still needed given that NP-traces are generally assumed to be subject to binding condition A as well.

| a. | Jani | heeft [VP ti | zichzelf/*hem/*die jongen | beschreven]. | |

| Jan | has | himself/him/that boy | described | ||

| 'Jan has described himself/him/that boy.' | |||||

| b. | [VP ti | zichzelf/*hem/*die jongen | beschreven]j | heeft | Jani tj. | |

| [VP ti | himself/him/that boy | described | has | Jan |

If NP-traces must indeed be bound, VP-topicalization constructions of the type in (478) also provide evidence in favor of reconstruction. Under the standard assumption that the clause-initial position can be filled by phrases only (and not by heads), the theme argument must have been extracted from the VP by NP-movement (nominal argument shift of the type discussed in Section 13.2) before the VP is topicalized. The VP thus contains a trace of the theme argument and reconstruction is needed in order for the trace to be bound by the moved noun phrase mijn huis'my house'; see Section 11.3.3, sub VIC, for more discussion.

| a. | Ze | hebben | mijn huis | nog | niet | geschilderd. | perfect tense | |

| they | have | my house | yet | not | painted | |||

| 'They havenʼt painted my house yet.' | ||||||||

| a'. | [VP ti | Geschilderd]j | hebben | ze | mijn huisi tj | nog | niet. | |

| [VP ti | painted | have | they | my house | yet | not | ||

| 'They havenʼt painted my house yet.' | ||||||||

| b. | Mijn huis | wordt | volgend jaar | geschilderd. | passive | |

| my house | is | next year | painted | |||

| 'My house will be painted next year.' | ||||||

| b'. | [VP ti | Geschilderd]j | wordt | mijn huisi volgend jaar tj. | |

| [VP ti | painted | is | my house next year | ||

| 'My house will be painted next year.' | |||||

The examples so far all involve topicalization of arguments, complementives, and VP, and we have seen that such cases exhibit reconstruction effects: binding possibilities are computed from the base position of the moved phrase. This does not seem to hold for adjuncts, however, as is clear from the contrast between the two examples in (479); if the adverbial clause in (479b) were interpreted in the same position as the adverbial clause in (479a), we would wrongly expect coreference between Jan and hij to be blocked by binding condition C in both cases. This contrast has given rise to the idea that examples such as (479b) are actually not derived by wh-movement, but involve base-generation of the adjunct in clause-initial position; that this is possible is then attributed to the fact that adjuncts are not selected by the verb and can consequently be generated externally to the lexical projection of the verb.

| a. | * | Hij | ging | naar de film | [omdat | Jan | moe | was]. |

| he | went | to the movie | because | Jan | tired | was |

| b. | [Omdat | Jan | moe | was], | ging | hij | naar de film. | |

| because | Jan | tired | was | went | he | to the movie | ||

| 'Because Jan was tired, he went to the movie.' | ||||||||

Note in passing that the lack of reconstruction cannot be demonstrated on the basis of binding condition B, as referential pronouns embedded in adverbial clause can always be coreferential with the subject of a matrix clause; this is shown in (480).

| a. | Jan | ging | niet | naar de film | [omdat | hij | moe | was]. | |

| Jan | went | not | to the movie | because | he | tired | was | ||

| 'Jan didnʼt go to the movie because he was tired.' | |||||||||

| b. | [Omdat hij moe was], | ging | Jan | niet | naar de film. | |

| because he tired was | went | Jan | not | to the movie | ||

| 'Because he was tired, Jan didnʼt go to the movie.' | ||||||

A similar lack of reconstruction can be observed in the examples in (481); cf. Van Riemsdijk & Williams (1981). In this case an argument is topicalized but the contrast between the two examples shows that the reconstruction effect is lacking: contrary to what would be expected if the topicalized phrase were interpreted in the position of its trace, the referential noun phrase Jan embedded in the relative clause can be coreferential with the pronoun hij in (481b). It is of course not possible to appeal to an argument-adjunct asymmetry in this case, but it has been suggested that the (optional) relative clause is an adjunct that can be generated after the object has undergone wh-movement; see Barss (2001) and Sportiche (2006) for details.

| a. | * | Hij | wil | [het boek | [dat Jan | gekocht | heeft]] | aan Marie | geven. |

| he | wants | the book | that Jan | bought | has | to Marie | give |

| b. | [Het boek | [dat | Jan gekocht | heeft]]i | wil | hij ti | aan Marie | geven. | |

| the book | that | Jan bought | has ` | wants | he | to Marie | give | ||

| 'The book that Jan has bought, he wants to give to Marie.' | |||||||||

The examples in (482) show again that the lack of reconstruction cannot be demonstrated on the basis of binding condition B, as referential pronouns embedded in a relative clause can be coreferential with the subject of a matrix clause.

| a. | Jan wil | [het boek | [dat | hij | gekocht | heeft]] | aan Marie | geven. | |

| Jan wants | the book | that | he | bought | has | to Marie | give | ||

| 'Jan wants to give the book that he has bought to Marie.' | |||||||||

| b. | [Het boek | [dat | hij | gekocht | heeft]]i | wil | Jan ti | aan Marie | geven. | |

| the book | that | he | bought | has | wants | Jan | to Marie | give | ||

| 'The book that he has bought, Jan wants to give to Marie.' | ||||||||||

The discussion of the data in this subsection has shown that a reconstruction effect obligatorily occurs if some argument, complementive or verbal projection is topicalized. Reconstruction effects are absent if an adverbial clause occupies the clause-initial position or if the topicalized phrase is modified by a relative clause.

Because wh-movement has a clear semantic import, the standard (but not uncontroversial) assumption is that it precedes the semantic interpretation of the clause. The fact that for the purpose of the binding theory formulated in (467) topicalized phrases behave as if they still occupy the position indicated by their traces has led to theories according to which wh-movement is at least partly undone before the semantic interpretation of the syntactic representation takes place; the technical term for this is Reconstruction. A more recent approach, which makes reconstruction superfluous, is Chomsky's (1995:ch.3) copy theory of movement, according to which movement is a copy-and-paste operation that leaves a phonetically empty copy (a copy that is not pronounced in the actual utterance) of the moved constituent in its original position. For convenience, we will follow general practice by maintaining the notion of reconstruction as a purely descriptive term. The core finding that all theories try to explain is that binding of nominal arguments should be formulated in terms of A-positions, that is, argument positions to which thematic roles, agreement features and/or case are assigned; movement into A'-positions (positions such as the clause-initial position that may also be occupied by non-arguments) does not affect the binding possibilities. We refer the reader to Barrs (2001), Sportiche (2006) and Salzmann (2006) for critical reviews and discussions of the various theoretical implementations of this insight.

The standard view seems to be that reconstruction effects are syntactic in nature, but there are grounds for doubting that these effects are part of syntax proper. In order to show this we have to make a brief digression on contrastive and hanging-topic left-dislocation; see Section 14.2 for a more extensive discussion. Left dislocation is characterized by the fact that there is some phrase preceding the clause-initial position, which is associated with a resumptive element elsewhere in the clause. The two types of left-dislocation constructions differ in the form and position of the resumptive element: hanging-topic left-dislocation constructions have a resumptive pronoun in the form of a referential pronoun such as hem'him, which is' located in the middle field of the clause, as in (483a); contrastive left-dislocation constructions have a resumptive pronoun in the form of a demonstrative pronoun such as die'that, which is' located in clause-initial position, as in (483b). Observe that we indicate the relation between the left-dislocated phrase and the resumptive pronoun by means of indices (just like the relation between a moved phrase and its trace).

| a. | Jani, | ik | heb | hemi | niet | gezien. | hanging-topic LD | |

| Jan | I | have | him | not | seen | |||

| 'Jan I havenʼt seen him.' | ||||||||

| b. | Jani, | diei | heb | ik ti | niet | gezien. | contrastive LD | |

| Jan | dem | have | I | not | seen | |||

| 'Jan I havenʼt seen him.' | ||||||||

At first sight, the examples in (484) seem to show that left dislocation differs from topicalization in that it does affect the binding possibilities. Van Riemsdijk & Zwarts (1997) and Vat (1997) suggest, however, that the unacceptability of the examples in (484) is due to the fact that resumptive pronouns are referential pronouns which are subject to binding condition B of the binding theory by themselves. In order to satisfy the binding conditions on the reflexive zichzelf'himself' the resumptive pronouns hem'him' and die'that' must take the subject Jan as a local antecedent, which results in a violation of binding condition B. Observe that the binding conditions for the resumptive pronoun die in (484b) should be computed from its original object position indicated by its trace in object position.

| a. | * | Zichzelfi, | Jan | bewondert | hemi | het meest. | hanging-topic LD |

| himself | Jan | admires | him | the most | |||

| Intended meaning: 'Jan admires himself the most.' | |||||||

| b. | * | Zichzelfi, | diei | bewondert | Jan ti | het meest. | contrastive LD |

| himself | dem | admires | Jan | the most | |||

| Intended meaning: 'Jan admires himself the most.' | |||||||

Violations of binding condition B induced by the resumptive pronouns themselves can be avoided if the reflexive/reciprocal pronoun is more deeply embedded in the topicalized phrase, as in the examples in (471). Their left-dislocation counterparts in (485) show that the two types of left dislocation exhibit different behavior in such cases; while the hanging-topic construction is rated as ungrammatical in Van Riemsdijk & Zwarts (1997) and Vat (1997), the contrastive left-dislocation construction is fully acceptable. The fact that the left-dislocated phrase can be interpreted in the position of the trace of the wh-moved demonstrative die has become known as the connectivity effect.

| a. | * | [Elkaars moeder]i, | zij | bewonderen | haari | het meest. | hanging topic LD |

| each.otherʼs mother | they | admire | her | the most | |||

| 'Each otherʼs mother they admire the most.' | |||||||

| b. | [Elkaars moeder]i, | diei | bewonderen | zij ti | het meest. | contrastive LD | |

| each.otherʼs mother | dem | admire | they | the most | |||

| 'Each otherʼs mother they admire the most.' | |||||||

Connectivity effects also arise in the left-dislocation counterparts of the topicalization construction in (472b) with a bound variable reading. Van Riemsdijk & Zwarts (1997) and Vat (1997) show that there is again a contrast between hanging-topic and contrastive left-dislocation.

| a. | * | [Zijn (eigen) ouders]i, | iedereen bewondert | zei | het meest. | hanging-topic LD |

| his own parents | everyone admires | them | the most |

| b. | [Zijn (eigen) ouders]i, | diei | bewondert | iedereen ti | het meest. | contrastive LD | |

| his own parents | dem | admires | everyone | the most |

For completeness' sake, consider the contrastive left-dislocation constructions in (487), which show again that the acceptability judgments on the contrastive left-dislocation constructions are more or less the same as in the corresponding topicalization constructions in (473b) and (474b).

| a. | * | Hemi/Die jongeni, | diei | bewondert | Jan ti | het meest. |

| him/that boy | dem | admires | Jan | the most |

| b. | (?) | Hemi/*Die jongeni, | diei | denkt | Jan | [dat | ik ti | het meest | bewonder]. |

| him/that boy | dem | thinks | Jan | that | I | the most | admire | ||

| 'Him, Jan thinks that I admire the most.' | |||||||||

The discussion above has shown that contrastive left-dislocation constructions exhibit connectivity effects which closely resemble the reconstruction effects found in topicalization constructions. Given this similarity, it is temping to provide a single theoretical account of the two types of effect. This might lead to the conclusion that there is some kind of matching effect in the sense that the demonstrative pronoun die simply takes over certain semantic properties of the left-dislocated phrase and transmits these to the position of its trace; however, this would go against the current idea that reconstruction effects follow from the copy theory of movement: the claim that movement is a copy-and-paste operation that leaves an actual copy of the moved constituent in its original position.

Alternatively, one might attempt to show that left-dislocated phrases are base-generated within the clause they are attached to and find their surface position by (a series of movements including) wh-movement. If such an analysis is feasible, we could maintain that reconstruction effects result from the copy-and-paste operation proposed by the copy theory of movement; see Grohmann (2003:ch.4) and De Vries (2009) for detailed proposals. This would immediately account for the differences in connectivity effects established in this subsection between hanging-topic and contrastive left-dislocation constructions: hanging-topic constructions have a resumptive pronoun in the middle field of the clause, and we can therefore safely conclude that they do not involve wh-movement, and we consequently expect connectivity effects to be absent. There are, however, two potential problems for this approach. First there does not seem to be independent evidence for assuming that left-dislocated phrases have ever occupied a clause-internal position. Second, this approach should provide a reasonable account for the fact that left-dislocated phrases may strand prepositions, while topicalized phrases (and wh-moved phrases in general) are normally not able to do that; see the contrast between the (a)- and (b)-examples in (488).

| a. | *? | Dat boek | heb | ik | lang | naar | gezocht. | topicalization |

| that book | have | I | long | for | looked |

| a'. | * | Wat | heb | je | lang | naar | gezocht? | question formation |

| what | have | you | long | for | looked |

| b. | Dat boek, | daar heb ik lang naar gezocht. | contrastive LD | |

| that book | that have I long for looked | |||

| 'that book, I have looked for it a long time.' | ||||

We will return to the question as to whether reconstruction and connectivity effects can be given a (more or less) unified treatment in the discussion of relativization in Subsection IV below.

Section 11.3.1.1, sub II, discussed the hypothesis that the obligatoriness of wh-movement in wh-questions follows from the fact that it is instrumental in deriving an operator-variable chain in the sense of predicate calculus. It has also shown that this hypothesis runs into problems with examples like (489a&b), in which the moved wh-phrase is complex: the resulting syntactic representations cannot be directly translated into the desired semantic representations in the primed examples, as only a subpart of the wh-moved phrase corresponds to the question operator plus restrictor: the possessive pronoun wiens'whose' translates into ?x [x: person]. The phenomenon of pied piping thus makes it impossible to assume a one-to-one relationship between the surface form of a sentence and its semantic representation by simply stating that wh-movement creates an operator-variable chain. Question formation thus provides us with an independent motivation for some form of reconstruction; it is needed to arrive at the proper semantic representations for sentences like (489a&b).

| a. | [Wiens boek]i | heeft | Peter ti | gelezen? | |

| whose book | has | Peter | read | ||

| 'Whose book has Peter read?' | |||||

| a'. | ?x [x: person] (Peter has read x's book) |

| b. | [Wiens vaders boek]i | heeft | Peter ti | gelezen? | |

| whose fatherʼs book | has | Peter | read | ||

| 'Whose fatherʼs book has Peter read?' | |||||

| b'. | ?x [x: person] (Peter has read x's father's book) |

It is, however, less easy to convincingly demonstrate reconstruction effects for wh-movement than for topicalization, as the predictions of the binding theory can only be checked for bound elements embedded in some noun phrase because interrogative pronouns are never reflexive/reciprocal themselves. Furthermore, examples like (490) are often quoted to support reconstruction, but they are completely unsuitable for this purpose; it has been argued that the picture noun foto may have an implied agentive PRO-argument which is obligatorily construed as coreferential with the subject Jan; see N2.2.5.2 for detailed discussion. If so, the reflexive is locally bound within the noun phrase by PRO in both examples.

| a. | Jan | heeft | [een PRO | foto van zichzelf] | genomen | |

| Jan | has | a | picture of himself | taken |

| b. | [Welke PRO | foto van zichzelf]i | heeft | Jan ti | genomen? | |

| which | picture of himself | has | Jan | taken |

In order to construct convincing cases of reconstruction based on binding condition A, one must make sure that there is no implied PRO-argument that can be construed as coreferential with the antecedent of the reflexive/reciprocal pronoun. On the default interpretation of the examples in (491) that Jan did not spread rumors about himself, (491b) may be a case in point.

| a. | Jan | vond | [dit gerucht over zichzelf] | het leukst. | |

| Jan | considered | this rumor about himself | the funniest | ||

| 'Jan considered this rumor about himself the funniest one.' | |||||

| b. | [Welk gerucht over zichzelf]i | vond | Jan ti | het leukst? | |

| which rumor about himself | considered | Jan | the funniest | ||

| 'Which rumor about himself considered Jan the funniest one?' | |||||

The bound variable reading of pronouns, which requires a c-commanding quantifier to be present, also indicates that reconstruction does apply. Without reconstruction example (492b) would be wrongly predicted not to allow this reading.

| a. | Iedereen | vond | de foto | van zijn (eigen) moeder | het mooist. | |

| everyone | considered | the picture | of his own mother | the most.beautiful | ||

| 'Everyone liked the picture of his (own) mother best.' | ||||||

| b. | De foto | van zijn (eigen) moeder | vond | iedereen | het mooist. | |

| the picture | of his own mother | considered | everyone | the most.beautiful | ||

| 'Everyone liked the picture of his (own) mother best.' | ||||||

Arguments based on binding condition B are somewhat delicate because referential personal pronouns embedded within a noun phrase can often be coreferential with the subject of their clause if they are phonetically reduced. This is illustrated by the examples in (493), both of which are accepted by many speakers if the pronoun is phonetically reduced but rejected if the pronoun is non-reduced. The crucial point is, however, that topicalization does not seem to affect the acceptability judgments.

| a. | Jan | vond | [dit gerucht over ʼm/*hem] | het leukst. | |

| Jan | considered | this rumor about him/him | the funniest | ||

| 'Jan considered this rumor about him the funniest one?' | |||||

| b. | [Welk gerucht over ʼm/*hem]i | vond | Jan ti | het leukst? | |

| which rumor about him/hem | considered | Jan | the funniest | ||

| 'Which rumor about him considered Jan the funniest one?' | |||||

The examples in (494) do provide straightforward evidence for reconstruction based on binding condition C; they are both unacceptable if the noun phrase die popster is construed as coreferential with Jan.

| a. | * | Jan | vond | [dit gerucht over die popster] | het leukst. |

| Jan | considered | this rumor about that pop.star | the funniest | ||

| 'Jan considered this rumor about that pop star the funniest one.' | |||||

| b. | * | [Welk gerucht over die popster]i | vond | Jan ti | het leukst? |

| which rumor about that pop-star | considered | Jan | the funniest | ||

| 'Which rumor about that pop star considered Jan the funniest one?' | |||||

Note that, as in the case of topicalization, reconstruction need not apply for noun phrases embedded in relative clauses; while Jan cannot be construed as coreferential with the subject pronoun hij in (495a), this is possible in (495b).

| a. | * | Hij | wil | [het boek | [dat Jan | gekocht | heeft]] | aan Marie | geven. |

| he | want | the book | that Jan | bought | has | to Marie | given | ||

| 'He wants to give the book that Jan has bought to Marie.' | |||||||||

| b. | [Welk boek | [dat | Jan | gekocht | heeft]]i | wil | hij ·ti | aan Marie | geven? | |

| which book | that | Jan | bought | has | wants | he | to Marie | give | ||

| 'Which book that Jan has bought does he want to give to Marie?' | ||||||||||

Despite the difficulty in constructing relevant examples, the arguments based on the bound variable reading of pronouns and binding condition C show conclusively that wh-questions exhibit similar reconstruction effects as topicalization constructions.

Reconstruction effects are even more difficult to establish in relative constructions than in wh -questions. We will see, however, that there is an additional twist to the discussion given that we find similar connectivity effects as discussed in Subsection IIB for contrastive left-dislocation constructions; this may shed more light on the question as to whether reconstruction and connectivity effects can be given a (more or less) unified account.

As with wh-questions, reconstruction for binding condition A is again difficult to establish because the reflexive/reciprocal pronoun must be embedded within a larger phrase: relative pronouns are never reflexive/reciprocal themselves. Moreover, because the relative pronoun is typically a possessive pronoun such as wiens'whose' in complex noun phrases, we expect that it will normally be construed as the antecedent of a reflexive/reciprocal pronoun within the wh-moved phrase; cf. Section N5.2.1.5. The impossibility of construing the subject as the antecedent of zichzelf in examples such as (496), in which the intended binding is again indicated by italics, therefore does not tell us anything about reconstruction.

| a. | de mani | [[wiensi boek over zichzelf]j | hij | wil tj | lezen] | |

| the man | whose book about himself | he | wants | read | ||

| 'the man whose book about himself he wants to read' | ||||||

| b. | * | de mani | [[wiensi boek over zichzelf]j | hij | wil tj | lezen] |

| the man | whose book about himself | he | wants | read |

Examples such as (497b) with a bound variable reading do seem to provide evidence for reconstruction, although some speakers may find it hard to give a judgment on this example due to its complexity.

| a. | Iedereen | zal | [Maries advies over zijn kinderen] | volgen. | |

| everyone | will | Marieʼs advice about his children | follow | ||

| 'Everyone will follow Marieʼs advice about his children.' | |||||

| b. | de vrouwi | [wiensi advies over zijn kinderen]j | iedereen tj | wil | volgen | |

| the woman | whose advice about his children | everyone | wants | follow | ||

| 'the woman whose advice about his children everyone will follow' | ||||||

Reconstruction for binding condition B is again difficult to establish because referential pronouns embedded within a noun phrase containing a possessive pronoun can normally be coreferential with noun phrases external to that noun phrase. Moreover, the acceptability of (498b) does not tell us anything about reconstruction because referential pronouns do not require a c-commanding antecedent.

| a. | Jan | negeerde | [Peters opmerking over hem]. | |

| Jan | ignored | Peterʼs remark about him |

| b. | de mani | [[wiensi opmerking over hem]j | Jan tj | negeerde] | |

| the man | whose remark about him | Jan | ignored | ||

| 'the man whose remarks about him Jan ignored' | |||||

For binding condition C it is possible to show that reconstruction effects do occur: the intended coreference relation is excluded in both examples in (499). The fact that referential noun phrases may normally have a non-c-commanding antecedent suggests that reconstruction must apply.

| a. | * | Jan | negeerde | [Peters opmerking over die jongen]. |

| Jan | ignored | Peterʼs remark about that boy |

| b. | * | de mani | [[wiensi opmerking over die jongen]j | Jan tj | negeerde] |

| the man | whose remark about that boy | Jan | ignored |

Despite the difficulty in constructing relevant examples, the arguments based on the bound variable reading of pronouns and binding condition C show conclusively that relative clauses exhibit similar reconstruction effects as wh-questions and topicalization constructions.

The discussion in the previous subsection has shown that reconstruction within relative clauses is indeed obligatory. The research on relative clauses that has aroused most interest is, however, not concerned with reconstruction effects of the type discussed above but with connectivity effects of the kind we also found in contrastive left-dislocation constructions; cf, subsection IIB.

The connectivity effect for binding condition A can be illustrated by means of example (500); on the default interpretation that the rumors are not spread by Jan himself, the reflexive pronoun zichzelf 'himself' can only be properly bound by Jan if the antecedent of the relative pronoun dat 'which' is interpreted in the position of the latter's trace.

| [[Het gerucht over zichzelf]i | [dati | Jan ti | het leukst | vond]] | was | dat | hij | opgegeten | was door een leeuw. | ||

| the rumor about himself | which | Jan | the funniest | considered | was | that | he | prt.-eaten | was by a lion | ||

| 'The rumor about himself Jan liked best was that he had been eaten by a lion.' | |||||||||||

Connectivity effects can also be illustrated by means of example (501) on its bound variable reading. Since this reading arises only if a quantifier binds (hence: c-commands) a referential pronoun, we have to assume that the antecedent of the relative pronoun die'which' is interpreted in the position of the latter's trace.

| [[De foto van zijn ouders]i | [diei | iedereen ti | koestert]] | is | die | van hun huwelijk. | ||

| the picture of his parents | which | everyone | cherishes | is | the.one | of their marriage | ||

| 'The picture of his parents that everyone cherishes is the one of their marriage.' | ||||||||

Establishing connectivity effects for binding condition B is again somewhat delicate because referential personal pronouns embedded within a noun phrase can often be coreferential with the subject of their clause if they are phonetically reduced. Example (493) has shown, however, that phonetically non-reduced pronouns do not easily allow this. The fact that we do not find the same contrast in the relative construction in (502) may go against the postulation of a connectivity effect, but we will leave this aside, as it is not clear whether we are really dealing with a syntactic restriction or with a restriction of some other type.

| [[Het gerucht over ʼm/hem]i | [dati | Jan ti | het leukst | vond]] | was | dat | hij | opgegeten | was door een leeuw. | ||

| the rumor about him/him | which | Jan | the funniest | considered | was | that | he | prt.-eaten | was by a lion | ||

| 'The rumor about him that Jan liked best was that he had been eaten by a lion.' | |||||||||||

An even more serious problem is that connectivity effects for binding condition C are not found in relative clauses: example (503) does readily allow an interpretation in which the noun phrase Jan and the subject pronoun of the relative clause are coreferential.

| [[Het gerucht over Jan]i | [dati | hij ti | het leukst | vond]] | was | dat | hij | opgegeten | was door een leeuw. | ||

| the rumor about Jan | which | he | the funniest | considered | was | that | he | prt.-eaten | was by a lion | ||

| 'The rumor about Jan that he liked best was that he had ben eaten by a lion.' | |||||||||||

The examples in this section lead to a somewhat ambivalent result: connectivity effects can be established for examples such as (500) and (501) involving binding condition A and the bound variable reading of pronouns, but not for examples like (503) involving binding condition C. This may lead to the conclusion that connectivity effects only occur in the case of local (clause- internal and NP-internal) syntactic dependencies. This may in fact be derived from the traditional view in generative grammar, currently embedded in Chomsky's (2008) phase theory, that there are no syntactic restrictions on non-local relationships. It should be noted, however, that such a conclusion may be problematic in view Salzmann's (2006: Section 2.2) observation that connectivity effects differ crucially from reconstruction effects in that the latter also occur with non-local restrictions.

In the theoretical literature of the last decade an ardent debate has been raging on the question as to whether the connectivity effects in relative clauses can be reduced to reconstruction. This debate finds its origin in Vergnaud (1974), where it was claimed that, descriptively speaking, the antecedent of the relative pronoun is base-generated within the relative clause, placed in initial position of the relative clause by means of wh-movement, and subsequently raised to its surface position in the main clause; for updated versions of this so-called promotion/raising analysis, we refer the reader to Kayne (1994), Bianchi (1999) and De Vries (2002). Despite its popularity, the promotion/raising analysis is not uncontroversial as it raises a large number of technical/theory-internal problems; cf. Boef (2013) for a recent review. For example, it is still not clear why the antecedent is able to strand prepositions under wh-movement, while this is normally impossible in run-of-the-mill cases of wh-movement like topicalization and question formation; see the contrast between the (a)- and (b)-examples in (504).

| a. | *? | Dat boek | heb | ik | lang | naar | gezocht. | topicalization |

| that boek | have | I | long | for | looked |

| a'. | * | Wat | heb | je | lang | naar | gezocht? | question formation |

| what | have | you | long | for | looked |

| b. | [Dat boek | waar | ik | lang | naar | gezocht | heb] | is terecht. | Relativization | |

| that book | where | I | long | for | looked | have | is found | |||

| 'That book which I have been looking for a long time has been found.' | ||||||||||

Furthermore, Salzmann (2006) points out that the differences between reconstruction and connectivity effects for binding conditions B and C discussed in this section are problematic for this analysis.

This section has discussed reconstruction effects for constructions derived by wh-movement. It has been shown that these effects can be detected in topicalization constructions, wh-questions and relative clauses. The results are given in Table 2; the question marks indicate that for independent reasons, reconstruction effects for binding condition A/B could not be established for the construction in question.

| topicalization | question formation | relativization | |

| binding condition A | + | ? | ? |

| bound variable reading | + | + | + |

| binding condition B | + | ? | ? |

| binding condition C | + | — | — |

We also discussed connectivity effects in contrastive left-dislocation and relative clause constructions, which are quite similar in nature to the reconstruction effects found in wh-movement constructions. The findings from this section are given in Table 3; the question mark indicates that for independent reasons the presence of connectivity effects for binding condition B could not be established.

| reconstruction effect | connectivity effect | |

| binding condition A | + | + |

| bound variable reading | + | + |

| binding condition B | + | ? |

| binding condition C | + | — |

The similarities between reconstruction and connectivity effects have given rise to a revival of Vergnaud's (1974) promotion/raising analysis of relative clause constructions, according to which the antecedent of the relative pronoun is base-generated within the relative clause, moved into clause-initial position by wh-movement and subsequently promoted/raised into its surface position in the main clause; we refer to Kayne (1994), Bianchi (1999), De Vries (2002) for discussion.

An advantage of the promotion/raising analysis is that reconstruction and connectivity effects can both be derived from the copy theory of movement, according to which movement is a copy-and-paste operation that leaves a phonetically empty copy of the moved constituent in its original position; no additional theoretical machinery is needed. Salzmann (2006) objects to analyses of this sort by pointing out that they incorrectly predict that reconstruction and connectivity effects are identical: that this is not the case is clear from the fact that while reconstruction effects for binding condition C are pervasive, connectivity effects for binding condition C do not occur. We can add to this that the analysis wrongly predicts preposition stranding to be impossible, as run-of-the-mill cases of wh-movement like topicalization and question formation do not allow this.

A potential problem for Salzmann's claim is that connectivity effects for binding condition C (as well as for binding condition B) do occur in the case of contrastive left-dislocation, as is clear from the examples in (505), which were already discussed in Subsection II. This suggests that even if we reject the promotion/raising analysis for relative clauses, we may still need an analysis based on wh-movement for contrastive left-dislocation (which would again leave us with the problem of preposition stranding mentioned above); see Grohmann (2003:ch.4), De Vries (2009). and Ott (2014) for proposals that meet this condition; we return to this issue in Section 14.2.

| a. | * | Jan | bewondert | die jongen | het meest. |

| Jan | admires | that boy | the most |

| a'. | * | Die jongeni, | diei | bewondert | Jan ti | het meest. |

| that boy | that | admires | Jan | the most |

| b. | * | Jan denkt | [dat | ik | die jongen | het meest | bewonder]. |

| Jan thinks | that | I | that boy | the most | admire |

| b'. | * | Die jongeni, | diei | denkt | Jan | [dat | ik ti | het meest | bewonder]. |

| that boy | dem | thinks | Jan | that | I | the most | admire |

We have confined ourselves in this section to a discussion of reconstruction effects related to binding. Reconstruction effects are, however, also found in other domains; for a detailed discussion of these domains, we refer the reader to Sportiche (2006) and Salzmann (2006: Section 2.2).

- 2001Syntactic reconstruction effectsBaltin, Mark & Collins, Chris (eds.)The handbook of contemporary syntactic theoryMalden (Mass)/OxfordBlackwell Publishing

- 2001Syntactic reconstruction effectsBaltin, Mark & Collins, Chris (eds.)The handbook of contemporary syntactic theoryMalden (Mass)/OxfordBlackwell Publishing

- 2001Syntactic reconstruction effectsBaltin, Mark & Collins, Chris (eds.)The handbook of contemporary syntactic theoryMalden (Mass)/OxfordBlackwell Publishing

- 1999Consequences of antisymmetry. Headed relative clausesnullnullBerlin/New YorkMouton de Gruyter

- 1999Consequences of antisymmetry. Headed relative clausesnullnullBerlin/New YorkMouton de Gruyter

- 2013Doubling in relative clauses. Aspects of morphosyntactic microvariation in DutchUniversity UtrechtThesis

- 1981Lectures on government and bindingnullStudies in generative grammar 9DordrechtForis Publications

- 1995The minimalist programnullCurrent studies in linguistics ; 28Cambridge, MAMIT Press

- 2008On phasesFreidin, Robert, Otero, Carlos P. & Zubizarreta, Maria Luisa (eds.)Foundational Issues in Linguistic Theory. Essays in Honor of Jean-Roger VergnaudCambridge, MA/OxfordMIT Press133-166

- 2003Prolific Domains. On the Anti-Locality of Movement DependenciesnullnullAmsterdam/PhiladelphiaJohn Benjamins Publishing Company

- 2003Prolific Domains. On the Anti-Locality of Movement DependenciesnullnullAmsterdam/PhiladelphiaJohn Benjamins Publishing Company

- 1994The antisymmetry of syntaxnullLinguistic inquiry monographs ; 25Cambridge, MAMIT Press

- 1994The antisymmetry of syntaxnullLinguistic inquiry monographs ; 25Cambridge, MAMIT Press

- 2014An ellipsis approach to contrastive left dislocationLinguistic Inquiry45269-303

- 1997Left dislocation in Dutch and the status of copying rules [originally written in 1974]Anagnostopoulou, Elena, Riemsdijk, Henk van & Zwarts, Frans (eds.)Materials on left dislocationAmsterdam/PhiladephiaJohn Benjamins Publishing Company13-54

- 1997Left dislocation in Dutch and the status of copying rules [originally written in 1974]Anagnostopoulou, Elena, Riemsdijk, Henk van & Zwarts, Frans (eds.)Materials on left dislocationAmsterdam/PhiladephiaJohn Benjamins Publishing Company13-54

- 1997Left dislocation in Dutch and the status of copying rules [originally written in 1974]Anagnostopoulou, Elena, Riemsdijk, Henk van & Zwarts, Frans (eds.)Materials on left dislocationAmsterdam/PhiladephiaJohn Benjamins Publishing Company13-54

- 2006Resumptive prolepis. A study in indirect A'-dependenciesUniversity of LeidenThesis

- 2006Resumptive prolepis. A study in indirect A'-dependenciesUniversity of LeidenThesis

- 2006Resumptive prolepis. A study in indirect A'-dependenciesUniversity of LeidenThesis

- 2006Resumptive prolepis. A study in indirect A'-dependenciesUniversity of LeidenThesis

- 2006Resumptive prolepis. A study in indirect A'-dependenciesUniversity of LeidenThesis

- 2006Reconstruction, binding and scopeEveraert, Martin & Riemsdijk, Henk van (eds.)The Blackwell companion to syntax4Malden, Ma/OxfordBlackwell Publishers35-93

- 2006Reconstruction, binding and scopeEveraert, Martin & Riemsdijk, Henk van (eds.)The Blackwell companion to syntax4Malden, Ma/OxfordBlackwell Publishers35-93

- 2006Reconstruction, binding and scopeEveraert, Martin & Riemsdijk, Henk van (eds.)The Blackwell companion to syntax4Malden, Ma/OxfordBlackwell Publishers35-93

- 1997Left Dislocation, connectedness and reconstruction [written in 1980]Anagnostopoulou, Elena, Riemdijk, Henk van & Zwart, Frans (eds.)Materials on Left DislocationJohn BenjaminsAmsterdam/Philadelphia67-92

- 1997Left Dislocation, connectedness and reconstruction [written in 1980]Anagnostopoulou, Elena, Riemdijk, Henk van & Zwart, Frans (eds.)Materials on Left DislocationJohn BenjaminsAmsterdam/Philadelphia67-92

- 1997Left Dislocation, connectedness and reconstruction [written in 1980]Anagnostopoulou, Elena, Riemdijk, Henk van & Zwart, Frans (eds.)Materials on Left DislocationJohn BenjaminsAmsterdam/Philadelphia67-92

- 1974French relative clausesMITThesis

- 1974French relative clausesMITThesis

- 2002The syntax of relativizationAmsterdamUniversity of AmsterdamThesis

- 2002The syntax of relativizationAmsterdamUniversity of AmsterdamThesis

- 2009The right and left periphery in DutchThe Linguistic Review26291-327

- 2009The right and left periphery in DutchThe Linguistic Review26291-327

- 1996Clitics, Scrambling, and Head Movement in DutchHalpern, Aaron L. & Zwicky, Arnold M. (eds.)Approaching second. Second position clitics and related phenomenaStanfordCSLI579-611