- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

Many semantic subclassifications have been proposed for the set-denoting adjectives, but most of them seem to have a rather arbitrary flavor. Nevertheless, some of these distinctions have been claimed to be syntactically relevant (especially in the realm of modification, which is extensively discussed in Chapter 3), which is why we will briefly discuss these distinctions in the following subsections. It should be kept in mind, however, that in principle many other distinctions can be made, for other purposes, and that the classes discussed below exhibit a considerable overlap; see Subsection III for discussion.

- I. Scales and scalar adjectives

- II. Absolute (non-scalar) adjectives

- III. The distinction between gradable and scalar adjectives

- IV. Stage/individual-level adjectives

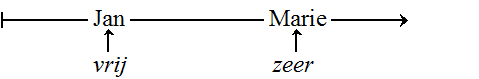

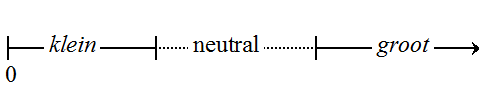

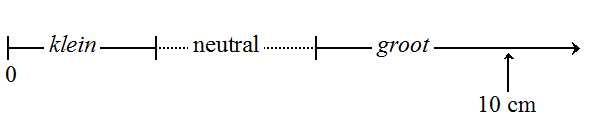

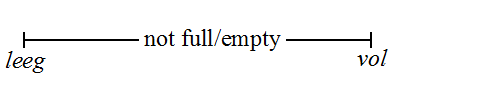

Many set-denoting adjectives are scalar. The primeless examples in (58) express that both Jan and Marie are part of the set denoted by the adjective ziek'ill', which will be clear from the fact that they imply the primed examples. The function of the intensifiers vrij'rather' and zeer'very' is to indicate that Jan and Marie do not exhibit the property of being ill to the same degree. This means that the possibility of adding an intensifier indicates that some scale is implied; the function of intensifiers vrij and zeer is to situate the illness of Jan and the illness of Marie at different places on this scale. This can be schematized as in (58c).

| a. | Jan is vrij ziek. | ⇒ | |

| Jan is rather ill |

| a'. | Jan is ziek. | |

| Jan is ill |

| b. | Marie is zeer ziek. | ⇒ | |

| Marie is very ill |

| b'. | Marie is ziek. | |

| Marie is ill |

| c. | Scale of illness: | |

|

The schema in (58c) indicates that Jan is less ill than Marie. Further, it indicates that there is some point to the left of Jan where we start to talk about illness; the scale is bounded at its left side. However, as long as the person involved stays alive, there is no obvious point on the right side of the scale where we stop talking about illness; the scale is unbounded at the right side. This subsection will discuss several types of scalar adjectives on the basis of the properties of the scales that they imply.

Many set-denoting adjectives come in antonym pairs, which can be situated on a single scale. Some examples are given in (59). The following subsections will show, however, that the scales implied by these antonym pairs may differ in various respects.

| a. | slecht | 'evil/bad' |

| a'. | goed | 'good' |

| b. | klein | 'small' |

| b'. | groot | 'big' |

| c. | vroeg | 'early' |

| c'. | laat | 'late' |

| d. | gezond | 'healthy' |

| d'. | ziek | 'ill' |

| e. | leeg | 'empty' |

| e'. | vol | 'full' |

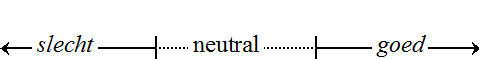

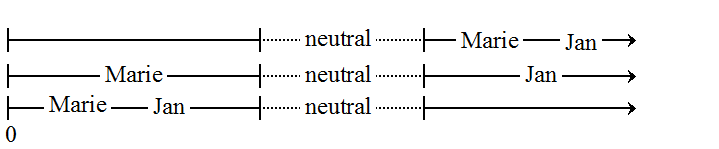

First consider the scale implied by the pair goed'good' and slecht'evil/bad', given in (60). The two adjectives each indicate a range on the scale, that is, they are both scalar. Further, the implied scale is unbounded on both sides. However, between the two ranges denoted by goed and slecht, there is a zone where neither of the two adjectives is applicable, and which we will call the neutral zone.

|

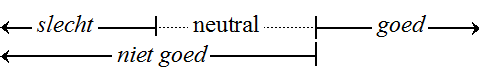

That there is a neutral zone is clear from the fact that slecht'evil/bad' and niet goed'not good' are not fully equivalent. The difference can be made clear by looking at the logical implications in (61a&b). The fact that slecht implies niet goed, but that niet goed does not imply slecht can be accounted for by making use of the scale of “goodness" in (60). As can be seen in (61c), niet goed covers a larger part of the scale than slecht: it includes the neutral zone.

| a. | Jan is slecht. | ⇒ | |

| Jan is evil |

| a'. | Jan is niet goed. | |

| Jan is not good |

| b. | Jan is niet goed. | ⇏ | |

| Jan is not good |

| b'. | Jan is slecht. | |

| Jan is evil |

| c. |  |

That we need to postulate a neutral zone is also clear from the fact that examples such as (62a) are not contradictory, but simply indicates that Janʼs goodness should be situated somewhere in the neutral zone. This is shown in (62b).

| a. | Jan is niet goed, | maar | ook | niet | slecht. | |

| Jan is not good | but | also | not | bad | ||

| 'Jan isnʼt good, but he isnʼt bad either.' | ||||||

| b. |  |

The scale of size in (63) implied by the measure adjectives klein'small' and groot'big' in (59b) is similar to the scale of “goodness" in most respects, but differs from it in that it is bounded on one side; the size of some entity cannot be smaller than zero. Observe that this implies that, unlike the scale of “goodness", the scale of size has a natural anchoring point. In this sense, adjectives like goed and slecht are more subjective than measure adjectives like klein and groot; see Subsection C below for more discussion.

|

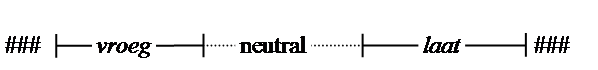

The implied scale can also be bounded on both sides. This is the case with the temporal scale implied by the adjectives vroeg'early' and laat'late' in (59c). When we assert that Jan is getting up early, that may be consistent with Jan getting up at 6:00 or 5:00 a.m., but presumably not with him getting up at 1:00 a.m. or at 11:00 p.m. Similarly, by asserting that Jan is getting up late, we may be saying that he is getting up at 11:00 a.m. or at 1:00 p.m., but presumably not that he is getting up at 11:00 p.m. or at 1:00 a.m. Beyond a certain point (which may be vaguely defined, and can perhaps be changed when the context provides information that favors that) the adjectives are simply no longer applicable (this is indicated by ### in (64)).

|

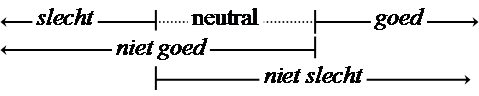

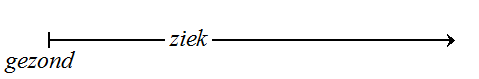

In the examples in the previous subsections, the two antonyms are both gradable. This need not be the case, however. The adjective gezond'healthy' in (59d), for instance, does not seem to be scalar itself; rather, it is absolute (see the discussion of (68)), and indicates one end of the scale. In other words, we may represent the scale of illness as in (65).

|

Many gradable adjectives that imply a scale that is bounded on one side are deverbal or pseudo-participles; cf. the primeless examples in (66) and (67). Their antonyms, which are situated at the boundary of the scale, are often morphologically derived by means of on- prefixation. In the case of the pseudo-participles occasionally no antonym exists, so that we can only express the negative counterpart by means of the negative adverb niet.

| a. | brandbaar | 'combustible' |

| a'. | onbrandbaar | 'incombustible' |

| b. | bereikbaar | 'attainable' |

| b'. | onbereikbaar | 'unattainable' |

| c. | begroeid | 'overgrown' |

| c'. | onbegroeid | 'without plants' |

| d. | toegankelijk | 'accessible' |

| d'. | ontoegankelijk | 'inaccessible' |

| a. | bekend met | 'familiar with' |

| a'. | onbekend met | 'unfamiliar with' |

| b. | bestand tegen | 'resistant to' |

| b'. | niet bestand tegen | 'not resistant to' |

| c. | gewond | 'wounded' |

| c'. | ongewond | 'not wounded' |

| d. | opgewassen tegen | 'up to' |

| d'. | niet opgewassen tegen | 'not up to' |

| e. | verwant aan | 'related to' |

| e'. | niet verwant aan | 'not related to' |

That gezond and the adjectives in the primed examples in (66) and (67) are not scalar but absolute is clear from the fact that they can be modified by adverbial phrases like absoluut'absolutely', helemaal'completely' and vrijwel'almost', as in (68). We show these examples with topicalization of the AP in order to block the reading in which absoluut/vrijwel is interpreted as a sentence adverb. The examples are perhaps stylistically marked but at least the cases with absoluut become fully acceptable if we add the negative adverb niet'not' at the end of the clause.

| a. | Absoluut/vrijwel | gezond | is Jan. | |

| absolutely/almost | healthy | is Jan |

| b. | Absoluut/vrijwel | onbrandbaar | is deze stof . | |

| absolutely/almost | incombustible | is this material |

| c. | Helemaal/vrijwel | onbekend | met onze gewoontes | is Jan. | |

| completely/almost | not.familiar | with our habits | is Jan |

The examples in (69) show that these adverbial phrases cannot be combined with scalar adjectives; cf. Section 1.3.2.2, sub II.

| a. | * | Absoluut/vrijwel | goed/klein/ziek | is Jan. |

| absolutely/almost | good/small/ill | is Jan |

| b. | * | Absoluut/vrijwel | brandbaar | is deze stof. |

| absolutely/almost | combustible | is this material |

| c. | * | Helemaal/vrijwel | bekend met onze gewoontes | is Jan. |

| completely/almost | familiar with our habits | is Jan |

For completeness’ sake note that the adjective gezond'healthy' can also be used as a scalar adjective, provided that it is the antonym of ongezond'unhealthy'. In this use, gezond cannot be modified by the adverbial phrases absoluut and vrijwel. This is shown in (70).

| * | Absoluut/vrijwel | gezond/ongezond | is spinazie. | |

| absolutely/almost | healthy/unhealthy | is spinach |

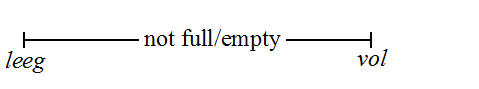

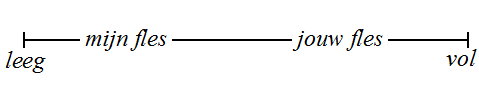

The fact that gezond (i.e., the antonym of ziek'ill') is not scalar shows that the placement of an antonym pair of adjectives on a scale is not sufficient to conclude that the adjectives are both scalar. In fact, they can both be absolute. This is the case with the adjectives leeg/vol'empty/full' in (59e); they both typically denote the boundaries of the implied scale. That leeg and vol are not scalar but absolute is clear from the fact that they can be modified by adverbial phrases like helemaal'totally', vrijwel'almost', etc.

| a. | Scale of “fullness" | |

|

| b. | Het glas | is helemaal/vrijwel | leeg/vol. | |

| the glass | is totally/almost | empty/full |

In the scales in (60), (63) and (64), we have indicated a neutral zone to which neither of the two adjectives is applicable. This zone is often more or less fixed for the speaker in question. With some adjectives, however, the neutral zone is more flexible and may be determined by the entity the adjectives are predicated of, or the context in which the adjectives are used. This holds in particular for the measure adjectives, of which some examples are given in (72).

| a. | dik | 'thick' |

| a'. | dun | 'thin' |

| b. | oud | 'old' |

| b'. | jong | 'young' |

| c. | groot | 'big' |

| c'. | klein | 'small' |

| d. | lang | 'tall/long' |

| d'. | kort | 'short/brief' |

| e. | hoog | 'high' |

| e'. | laag | 'low' |

| f. | zwaar | 'heavy' |

| f'. | licht | 'light' |

| g. | breed | 'wide' |

| g'. | smal | 'narrow' |

That the placement of the neutral zone, that is, that the interpretation of the measure adjectives depends on the argument the adjective is predicated of can be demonstrated by means of the examples in (73a) and (73b). Below, we will discuss the examples with the adjective groot, but the discussion is also applicable to klein.

| a. | Deze muis | is klein/groot. | |

| this mouse | is small/big |

| b. | Deze olifant | is klein/groot. | |

| the elephant | is small/big |

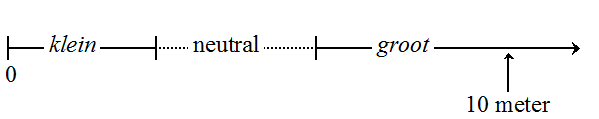

Although groot can be predicated of both the noun phrase deze muis'this mouse' and the noun phrase deze olifant'this elephant', it is clear that the two entities these noun phrases refer to cannot be assumed to be of a similar size: the mouse is considerably smaller than the elephant. This is due to the fact that the placement of the neutral zone on the implied scales of size differs. In the case of mice the scale will be expressed in term of centimeters, as in (74a), while in the case of elephants the scale will instead be expressed in meters, as in (74b).

| a. | Scale of size for mice in centimeters: | |

|

| b. | Scale of size for elephants in meters: | |

|

This shows that the placement of the neutral zone is at least partly determined by the argument the adjective is predicated of; it indicates the “normal" or “average" size of mice/elephants. In other words, examples such as (73) implicitly introduce a comparison class, namely the class of mice/elephants, which determines the precise position of the neutral zone on the implied scale. Often, a voor-PP can be used to make the comparison class explicit, and clarify the intended neutral zone, as in (75).

| Jan is groot | voor een jongen | van zijn leeftijd. | ||

| Jan is big | for a boy | of his age |

The comparison class and, hence, the neutral zone are not fully determined by the argument the adjective is predicated of; the context may also play a role. If we are discussing mammals in general, the statement in (76a) is true while the statement in (76b) is false: the comparison class is constituted by mammals, and therefore the neutral zone is determined by the average size of mammals, and Indian Elephants are certainly bigger than that. However, if we discuss the different subspecies of elephants, the statement in (76a) is false while the statement in (76b) is true: the comparison class is constituted by elephants, and the Indian Elephant is small compared to the African Elephant.

| a. | De Indische Olifant | is groot. | |

| the Indian Elephant | is big |

| b. | De Indische Olifant | is klein. | |

| the Indian Elephant | is small |

Although the placement of the neutral zone on the scale implied by the measure adjective depends on extra-linguistic information, the scale itself can be considered objective in the sense that once speakers have established the neutral zone, they can objectively establish whether a certain statement is true or false. The fact that the scale implied by the measure adjectives is objective is also supported by the fact that (in some cases) the precise position on the scale can be indicated by means of nominal measure phrases like twee dagen and twintig meter in (77).

| a. | Dit poesje | is twee dagen | oud. | |

| this kitten | is two days | old |

| b. | De weg | is twintig meter | lang. | |

| the road | is twenty meters | long |

In the case of adjectives like lelijk/mooi'ugly/beautiful' and saai/boeiend'boring/exciting', on the other hand, establishing the precise position of the relevant entities on the implied scale is a more subjective matter; in fact, it can depend entirely on the language user, which can be emphasized by embedding the adjective under the verb vinden'consider', as in the (a)-examples in (78). Occasionally, the entity whose evaluation is assumed can be syntactically expressed by means of a voor-PP; some examples are given in the (b)-examples.

| a. | Ik | vind | De Nachtwacht | lelijk/mooi. | |

| I | consider | The Night Watch | ugly/beautiful |

| a'. | Ik | vind | Shakespeares dramaʼs | saai/boeiend. | |

| I | consider | Shakespeareʼs tragedies | boring/exciting |

| b. | Dit gereedschap | is handig | voor een timmerman. | |

| this tool | is handy | for a carpenter | ||

| 'These tools are handy for a carpenter.' | ||||

| b'. | Dit boek | is interessant | voor elke taalkundige. | |

| this book | is of.interest | to every linguist |

The pairs of measure adjectives in (72) can be considered true antonyms. This is clear from the fact that the two (a)-examples in (79) are fully equivalent. However, this equivalence does not seem to hold for the subjective adjectives in the (b)-examples, which suggests that the comparative forms mooier and lelijker are not true but quasi-antonyms.

| a. | Jan is groter dan Marie. | ⇔ | |

| Jan is bigger than Marie |

| a'. | Marie is kleiner dan Jan. | |

| Marie is smaller than Jan |

| b. | De Nachtwacht | is mooier dan | De anatomieles. ⇎ | |

| The Night Watch | is more beautiful than | The Anatomy Lesson |

| b'. | De anatomieles | is lelijker dan | De Nachtwacht. | |

| The Anatomy Lesson | is uglier than | The Night Watch |

This difference may be related to the following observation. The use of the comparative form of objective adjectives like klein'small' and groot'big' in the (a)-examples of (79) does not necessarily imply that the argument the adjective is predicated of is actually small or big. The use of the comparative form of the subjective adjectives mooi'beautiful' and lelijk'ugly', on the other hand, at least strongly suggest that the argument the adjective is predicated of is indeed beautiful or ugly. This difference between objective and subjective adjectives may be lexically encoded; reasons for assuming this will be given in Subsection F below.

For completeness' sake, it can be observed that the true antonym of mooier is the comparative form minder mooi'less beautiful', as is clear from the fact that the equivalency does hold between (80a) and (80b). The true antonymy relation of course also holds for groter'bigger' and minder groot'less big'.

| a. | De Nachtwacht | is mooier dan | De anatomieles. ⇔ | |

| The Night Watch | is more beautiful than | The Anatomy Lesson |

| b. | De anatomieles | is minder mooi | dan | De Nachtwacht. | |

| The Anatomy Lesson | is less beautiful | than | The Night Watch |

The examples in (77) have already shown that the measure adjectives can be modified by means of a nominal measure phrase. However, for each antonym pair in (72), only the adjective in the primeless example can be used. Some examples are given in (81). Observe that the acceptable example in (81a) does not express the fact that the kitten is old; on the contrary, it is quite young, which can be emphasized by using the evaluative particle pas'only'. Therefore, it is clear that the adjective oud has lost the antonymous part of its meaning. The same thing holds for the adjective lang in (81b). Since these adjectives have lost this part of their meaning, oud and lang can be considered as neutral forms of the relevant pairs; the adjectives jong and kort cannot be used in this neutral way.

| a. | Het poesje | is (pas) | twee dagen | oud/%jong. | |

| the kitten | is only | two days | old/young |

| b. | De weg | is (maar) | twintig meter | lang/%kort. | |

| the road | is only | twenty meters | long/short |

Similar conclusions can be drawn from the interrogative sentences in (82): the neutral form oud/lang gives rise to a perfectly natural question and does not presuppose that the subject of the clause should be characterized as being old/long, whereas the non-neutral form jong/kort gives rise to a marked result and seems to express the presupposition that the kitten is young/the road is short.

| a. | Hoe oud/%jong | is het poesje? | |

| how old/young | is the kitten |

| b. | Hoe lang/%kort | is deze weg? | |

| how long/short | is this road |

In this context it is also relevant to observe that only the neutral forms of the measure adjectives can be the input of the morphological rule that derives nouns from adjectives by suffixation with -te. The formation *oudte in (83c) is probably blocked by the existing noun leeftijd 'age' . See Section 3.1.2, sub II, for more discussion of measure adjectives.

| a. | breedte | 'width' |

| a'. | *smalte |

| b. | dikte | 'thickness' |

| b'. | *dunte |

| c. | *oudte | 'age' |

| c'. | *jongte |

| d. | lengte | 'length' |

| d'. | *kortte |

| e. | hoogte | 'height' |

| e'. | #laagte |

| f. | zwaarte | 'weight' |

| f'. | *lichtte |

The adjectives in (84) exhibit a behavior similar to the measure adjectives in (82): the primeless examples are unmarked, and do not presuppose that the property denoted by the adjective is applicable; the primed examples, on the other hand, are marked, and strongly suggest that the property denoted by the adjective is applicable.

| a. | Hoe schoon | is de keuken? | |

| how clean | is the kitchen |

| a'. | % | Hoe vies | is de keuken? |

| how dirty | is the kitchen |

| b. | Hoe veilig | is die draaimolen? | |

| how safe | is that merry-go-round |

| b'. | % | Hoe onveilig | is die draaimolen? |

| how unsafe | is that merry-go-round |

Often, the subjective adjectives not only imply a subjective scale, but also express a negative or positive evaluation. Of the pair slecht'bad/evil' and goed'good', the first adjective clearly denotes a negatively valued property, whereas the latter denotes a positively valued property. The examples in (85) show that this distinction is also reflected in their modification possibilities: the primeless examples contain negatively valued adjectives, and modification by the elements knap'quite' and flink'quite' is possible; the primed examples, on the other hand, contain positively valued adjectives and modification by knap and flink is excluded.

| a. | knap | brutaal/moeilijk/lastig/ongehoorzaam | |

| quite | cheeky/difficult/troublesome/disobedient |

| a'. | * | knap | beleefd/makkelijk/eenvoudig/gehoorzaam |

| pretty | polite/easy/simple/obedient |

| b. | flink | moeilijk/lastig/ongehoorzaam | |

| quite | difficult/troublesome/disobedient |

| b'. | * | flink | makkelijk/eenvoudig/gehoorzaam |

| quite | easy/simple/obedient |

The examples in (86) show that litotes (the trope in literary and formal language by which one emphasizes a property by means of the negation of its antonym) also requires an adjective denoting a negatively valued property; if the adjective denotes a positively valued property, as in the primed examples, the desired interpretation does not normally arise; a notable exception is colloquial Daʼs niet goed!, in which the deictic force of the demonstrative has bleached; cf. English Thatʼs not good! (Carole Boster, p.c.).

| a. | Dat boek is niet slecht. | |

| that book is not bad | ||

| 'That is very good.' |

| a'. | # | Dat boek | is niet goed. |

| that book | is not good | ||

| Not: 'That is very bad.' | |||

| b. | Hij | is niet lelijk. | |

| he | is not ugly | ||

| 'Heʼs quite handsome.' | |||

| b'. | # | Hij | is niet knap. |

| he | is not handsome | ||

| Not: 'Heʼs quite ugly.' | |||

The modifier wel 'rather' , on the other hand, requires an adjective that denotes a positively valued property. This is illustrated in (87). Note that the primed examples are fully acceptable if wel is interpreted as the affirmative marker wel ; the two forms differ in that the affirmative marker receives accent, whereas the modifier does not. These uses of niet and wel in (86) and (87) are more extensively discussed in Section 3.3, sub II.

| a. | Jan is wel | aardig. | |

| Jan is wel | kind | ||

| 'Jan is rather kind.' | |||

| a'. | * | Jan is wel | onaardig. |

| Jan is wel | unkind |

| b. | Hij | is wel | knap. | |

| he | is wel | handsome | ||

| 'Heʼs rather handsome.' | ||||

| b'. | * | Hij | is wel | lelijk. |

| he | is wel | ugly |

Occasionally, the modifier is sensitive both to the positive/negative value of the adjective and the syntactic environment. The modifier een beetje'a bit', for example, requires a negatively valued adjective in declarative clauses (or an adjective that does not have an antonym such as verliefd'in love'). In questions and imperatives, on the other hand, this modifier prefers an adjective that denotes a positively valued property.

| a. | Hij | is | een beetje | onaardig/*?aardig. | |

| he | is | a bit | unkind/kind |

| b. | Is | hij | een beetje | aardig/?onaardig? | |

| is | he | a bit | kind/unkind |

| c. | Wees | een beetje | aardig/#onaardig! | |

| be | a bit | kind/unkind |

This subsection discusses the fact that negative polarity items can be licensed by the subset of antonymous adjectives that were called true antonyms in subsection C above. In order to be able to do that we should first discuss certain logical properties of these adjectives. True antonyms have the defining property that they allow the inference in (89a), in which A and A' represent antonymous adjectives; cf, subsection C. In (89b), we repeat example (79a): if we say that Jan is bigger than Marie, we may conclude that Marie is smaller than Jan, and, similarly, if we claim that Marie is smaller than Jan, we may conclude that Jan is bigger than Marie. This equivalency does not hold for quasi-antonymous adjectives like mooi'beautiful' and lelijk'ugly'; see example (79b) for discussion.

| a. | x is more A than y ⇔ y is more A' than x |

| b. | Jan is groter dan Marie. ⇔ | Marie is kleiner dan Jan. | |

| Jan is bigger than Marie | Marie is smaller than Jan |

True and quasi-antonymous adjectives are similar in that the implications in (90a) do not hold for either, which is due to the fact that in both cases the implied scale may have a neutral zone. This was already discussed for the quasi-antonymous adjectives slecht'bad' and goed'good' in Subsection A, so we confine ourselves here to giving similar examples for the true antonymous adjectives groot'big' and klein'small'.

| a. | not A ⇏A'; not A' ⇏A |

| b. | Jan is niet groot. ⇏ | Jan is klein. | |

| Jan is not big | Jan is small |

| b'. | Jan is niet klein. ⇏ | Jan is groot. | |

| Jan is not good | Jan is evil |

Despite the fact that the implications in (90a) do not hold, we will show in this subsection that for the true antonyms above, the pair not A and A' as well as the pair not A' and A do exhibit certain similarities in semantic behavior, which may be relevant when it comes to the licensing of negative polarity items like ook maar iets'anything'. In order to demonstrate this, we have selected the adjectives in (91). These adjectives were chosen because they may take a clausal complement, which is crucial for our purposes below because negative polarity items like ook maar iets are normally only possible in embedded clauses.

| a. | gemakkelijk | 'easy' |

| a'. | moeilijk | 'difficult' |

| b. | verstandig | 'clever' |

| b'. | onverstandig | 'foolish' |

| c. | veilig | 'safe' |

| c'. | gevaarlijk | 'dangerous' |

Consider the examples in (92). In the primeless examples, the complement clause refers to a wider set of events than the complement in the primed examples; the addition of an adverb in the latter cases makes the event the complement clause refers to more specific, and hence applicable to a smaller number of situations. For example, there are many occasions in which a problem is solved, but only in a subset of those occasions is the problem solved fast.

| a. | Het | is gemakkelijk | om | dat probleem | op | te lossen. | |

| it | is easy | comp | that problem | prt. | to solve | ||

| 'Itʼs easy to solve that problem.' | |||||||

| a'. | Het | is gemakkelijk | om | dat probleem | snel | op | te lossen. | |

| it | is easy | comp | that problem | quickly | prt. | to solve | ||

| 'Itʼs easy to solve that problem fast.' | ||||||||

| b. | Het | is verstandig | om | een boek | voor Peter | te kopen. | |

| it | is clever | comp | a book | for Peter | to buy | ||

| 'Itʼs clever to buy a book for Peter.' | |||||||

| b'. | Het | is verstandig | om | hier | een boek | voor Peter | te kopen. | |

| it | is clever | comp | here | a book | for Peter | to buy | ||

| 'Itʼs clever to buy a book for Peter here.' | ||||||||

| c. | Het | is veilig | om | hier | over | te steken. | |

| it | is safe | comp | here | prt. | to cross | ||

| 'Itʼs safe to cross the road here.' | |||||||

| c'. | Het | is veilig | om | hier | met je ogen dicht | over | te steken. | |

| it | is safe | comp | here | with your eyes closed | prt. | to cross | ||

| 'Itʼs safe to cross the road here with your eyes closed.' | ||||||||

Now, it is important to note that one cannot conclude from the truth of the primeless examples that the primed examples are true as well. However, one could conclude from the truth of the primed examples that the primeless ones are true as well. The environments in (92), in which an expression like snel oplossen'to solve quickly' can be replaced by a more general one like oplossen'to solve' without changing the truth-value of the expression, are called upward entailing.

The inferences change radically if we replace the adjectives in (92) by their antonyms, as in (93). Now, we may conclude from the truth of the primeless examples that the primed examples are true as well, and not vice versa. The environments in (93), in which an expression like oplossen'to solve' can be replaced by a more specific one like snel oplossen'to solve quickly' without changing the truth-value of the expression, are called downward entailing.

| a. | Het | is moeilijk | om | dat probleem | op | te lossen. | |

| it | is difficult | comp | that problem | prt. | to solve | ||

| 'Itʼs difficult to solve that problem.' | |||||||

| a'. | Het | is moeilijk | om | dat probleem | snel | op | te lossen. | |

| it | is difficult | comp | that problem | quickly | prt. | to solve | ||

| 'Itʼs difficult to solve that problem fast.' | ||||||||

| b. | Het | is onverstandig | om | een boek | voor Peter | te kopen. | |

| it | is foolish | comp | a book | for Peter | to buy | ||

| 'Itʼs foolish to buy a book for Peter.' | |||||||

| b'. | Het | is onverstandig | om | hier | een boek | voor Peter | te kopen. | |

| it | is foolish | comp | here | a book | for Peter | to buy | ||

| 'Itʼs foolish to buy a book for Peter here.' | ||||||||

| c. | Het | is gevaarlijk | om | hier | over | te steken. | |

| it | is dangerous | comp | here | prt. | to cross | ||

| 'Itʼs dangerous to cross the road here.' | |||||||

| c'. | Het | is gevaarlijk | om | hier | met je ogen dicht | over | te steken. | |

| it | is dangerous | comp | here | with your eyes closed | prt. | to cross | ||

| 'Itʼs dangerous to cross the road here with your eyes closed.' | ||||||||

From the examples in (92) and (93) we may conclude that the adjectives in the primeless examples of (91) create upward entailing environments, whereas the adjectives in the primed examples of (91) create downward entailing environments. It should be observed that negation is able to change this property into its reverse. If we add the adverb niet'not' to the examples in (92) the environments become downward entailing, and if we add niet to the examples in (93) the environments becomes upward entailing. For example, niet gemakkelijk'not easy' in (94a&a') behaves just like moeilijk'difficult' in (93a&a'), and niet moeilijk'not difficult' in (94b&b') behaves just like gemakkelijk'easy' in (92a&a') in this respect.

| a. | Het | is niet gemakkelijk | om | dat probleem | op | te lossen. | |

| it | is not easy | comp | that problem | prt. | to solve | ||

| 'It isnʼt easy to solve that problem.' | |||||||

| a'. | Het | is niet gemakkelijk | om | dat probleem | snel | op | te lossen. | |

| it | is not easy | comp | that problem | quickly | prt. | to solve | ||

| 'It isnʼt easy to solve that problem fast.' | ||||||||

| b. | Het | is niet moeilijk | om | dat probleem | op | te lossen. | |

| it | is not difficult | comp | that problem | prt. | to solve | ||

| 'It isnʼt difficult to solve that problem.' | |||||||

| b'. | Het | is niet moeilijk | om | dat probleem | snel | op | te lossen. | |

| it | is not difficult | comp | that problem | quickly | prt. | to solve | ||

| 'It isnʼt difficult to solve that problem fast.' | ||||||||

Another respect in which niet gemakkelijk and moeilijk, and niet moeilijk and gemakkelijk behave in a similar way concerns the licensing of negative polarity items like ook maar iets'anything'. These elements are only licensed in downward entailment environments. Therefore, they can occur in contexts like (95), but not in contexts like (96).

| a. | Het is moeilijk/niet gemakkelijk | om | ook maar iets | te zien | van de wedstrijd. | |

| it is difficult/not easy | comp | anything | to see | of the match | ||

| 'Itʼs difficult/not easy to see anything of the match.' | ||||||

| b. | Het is onverstandig/niet verstandig | om | er | ook maar iets | over | te zeggen. | |

| it is foolish/not clever | comp | there | anything | about | to say | ||

| 'Itʼs foolish/not clever to say anything about it.' | |||||||

| c. | Het | is gevaarlijk/niet veilig | om | ook maar | even | te aarzelen. | |

| it | is dangerous/not safe | comp | ook maar | a moment | to hesitate | ||

| 'Itʼs dangerous/not safe to hesitate even for a second.' | |||||||

| a. | * | Het is gemakkelijk/niet moeilijk | om | ook maar iets | te zien | van de wedstrijd. |

| it is easy/not difficult | comp | anything | to see | of the match |

| b. | * | Het is verstandig/niet onverstandig | om | er | ook maar iets | over | te zeggen. |

| it is clever/not foolish | comp | there | anything | about | to say |

| c. | * | Het is veilig/niet gevaarlijk | om | ook maar | even | te aarzelen. |

| it is safe/not dangerous | comp | ook maar | a moment | to hesitate |

This means that although the phrase not A is not semantically equivalent to A', we may conclude from the data above that in the case of truly antonymous adjectives. the two give rise to the same kind of environment: if A' creates a downward or upward entailment environment, the same thing holds for not A.

Not all set-denoting adjectives are scalar. Typical examples of absolute adjectives are dood'dead' and levend'alive'. The two adjectives denote complementary sets of entities that have the absolute property of being dead/alive. That the adjectives are not scalar is clear from the fact that they (normally) cannot be modified by intensifiers like vrij'rather' or zeer'very'. Similarly, comparative/superlative formation is normally excluded.

| a. | % | een | vrij | dode | plant |

| a | rather | dead | plant |

| b. | % | een | zeer | levende | hond |

| a | very | living | dog |

| a'. | % | een | dodere | plant |

| a | more.dead | plant |

| b'. | % | een | levender | hond |

| a | more.living | dog |

| a''. | % | de | doodste | plant |

| the | most.dead | plant |

| b''. | % | de | levendste | hond |

| the | most.living | dog |

This does not imply, however, that modification is excluded categorically. Consider the examples in (98). The modifiers in (98a), which we may call approximatives, indicate that the argument that the adjective dood is predicated of has nearly reached the condition that can be denoted by the adjective. The approximatives differ from the intensifiers in (98b) in that one has to conclude from (98a) that the plant is not dead (yet), whereas one must conclude from (98b) that the plant is beautiful. The approximatives in (98a) have the absolute counterpart helemaal'completely' in (98c), which emphasizes that the predicate does apply.

| a. | Die plant is vrijwel/zo goed als | dood. | ⇒ | |

| that plant is almost/as good as | dead |

| a'. | Die plant is niet dood. | |

| that plant is not dead |

| b. | Die plant is vrij/zeer mooi. | ⇒ | |

| that plant is rather/very beautiful |

| b'. | Die plant is mooi. | |

| that plant is beautiful |

| c. | Die plant is helemaal dood. | ⇒ | |

| that plant is completely dead |

| c'. | Die plant is dood. | |

| that plant is dead |

The examples in (99) shows that the approximative and absolute modifiers in (98) normally cannot be combined with scalar adjectives.

| a. | * | Die plant | is vrijwel/zo goed als/helemaal | mooi. |

| that plant | is almost/as good as/completely | beautiful |

| b. | * | Jan is vrijwel/zo goed als/helemaal | aardig. |

| Jan is almost/as good as/completely | nice |

It should be noted, however, that it is not always crystal clear whether we have to classify a certain adjective as absolute or scalar. The adjective vol'full' may be a good example of a case where the distinction is somewhat vague. The examples in (100) show that this adjective can be modified by approximative and absolute adverbs, which suggests that it should be considered an absolute adjective.

| a. | De fles | is vrijwel/zo goed als | vol. | |

| the bottle | is almost/as good as | full |

| b. | De fles | is helemaal | vol. | |

| the bottle | is completely | full |

In the examples in (101), however, the adjective vol can also be modified by intensifiers like vrij'quite' or erg'very', which is a hallmark of scalar adjectives. This paradox may be due to the fact that in everyday practice vol is generally not used in the sense of “100% filled". For example, a cup of coffee is normally vol if it is filled to, say, 90 percent; if it is filled up to the rim, it would actually be called too full. It seems that intensifiers can be used to specify the range between 90 and 100 percent full. This suggests that, although vol is normally used as an absolute adjective, it can also be used as a scalar adjective when we discuss the periphery of the scale.

| a. | Dit kopje | is vol. | filled to 90 percent | |

| this cup | is full |

| b. | Dit kopje | is vrij vol. | filled to nearly 90 percent | |

| this cup | is quite full |

| c. | Dit kopje | is erg vol. | filled to more than 90 percent | |

| this cup | is very full |

| d. | Dit kopje | is te vol. | filled to much more than 90 percent | |

| this cup | is too full |

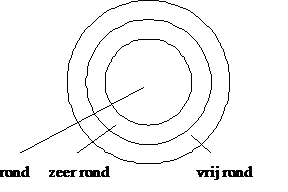

This subsection argues that we should make a distinction between gradable and scalar adjectives. A crucial role in this discussion will be played by absolute adjectives that do not come in antonymous pairs, such as the color adjectives rood 'red' , geel 'yellow' , blauw 'blue' , etc., and adjectives that denote geometrical properties like vierkant 'square' , rond 'round' , driehoekig 'triangular' . It will be shown that these adjective are gradable but not scalar.

Gradable adjectives are generally defined as adjectives that can be modified by means of an intensifier like vrij/zeer 'rather/very' and undergo comparative and superlative formation, as in (102). These are also typical properties of the class of scalar adjectives; example (58) in Section 1.3.2.2, sub I, has already shown that the intensifiers determine the position of the logical subject of the adjective on the implied scale, and example (107) below will show that the comparative/superlative forms determine the relative position of the compared entities on the implied scale.

| a. | Deze hond | is vrij/zeer intelligent. | |

| this dog | is rather/very intelligent |

| a'. | Deze hond | is intelligenter/het intelligentst. | |

| this dog | is more/the most intelligent |

| b. | Deze ballon | is vrij/zeer groot. | |

| this balloon | is rather/very big |

| b'. | Deze ballon | is groter/het grootst. | |

| this balloon | is bigger/the biggest |

However, this does not necessarily imply that the terms scalar and gradable adjectives are equivalent. Consider the examples in (103) that involve the geometrical adjective rond'round'. Just like the adjective dood'dead', the adjective rond'round' can be modified by the approximate adverb vrijwel'almost' and the absolute adverb helemaal'perfectly', from which we may conclude that rond is an absolute adjective; cf. the discussion of (98).

| a. | De tafel | is vrijwel | rond. | |

| the table | is almost | round | ||

| 'The table is nearly perfectly round.' | ||||

| b. | De tafel | is helemaal | rond. | |

| the table | is perfectly | round | ||

| 'The table is perfectly round.' | ||||

However, example (104a) shows that the adverbs vrij'rather' and zeer'very' can also be used. If this is indeed a defining property of gradable adjectives, we have to conclude that rond is gradable. The same thing would follow from (104b), which shows that rond is eligible for comparative and superlative formation. Consequently, if the terms scalar and gradable were identical, we would end up with a contradiction: the adjective rond would then be both scalar and absolute (non-scalar).

| a. | Jans gezicht | is vrij/zeer | rond. | |

| Janʼs face | is rather/very | round |

| b. | Jans gezicht | is ronder/het rondst. | |

| Janʼs face | is rounder/the roundest |

If one were to insist on maintaining that the notions scalar and gradable are the same, one could argue that, despite appearances, we are actually not dealing with intensifiers in (104a). As we have seen in (58c), intensifiers are used to specify the place on the (range of the) scale implied by the scalar adjective. From this it follows that vrij/zeer A implies that A holds. This is shown in (105a) for example (102a). However, this implication does not hold for example (104a); on the contrary, the implication is that the geometrical property denoted by rond does not hold perfectly.

| a. | Deze hond | is vrij/zeer | intelligent. | ⇒ | |

| this dog | is rather/very | intelligent |

| a'. | Deze hond | is intelligent. | |

| this dog | is intelligent |

| b. | Jans gezicht | is vrij/zeer | rond. | ⇒ | |

| Janʼs face | is rather/very | round |

| b'. | Jans gezicht | is niet rond. | |

| Janʼs face | is not round |

In this respect, the adverbs vrij and zeer in (105b) behave like the approximatives discussed in Section 1.3.2.2, sub II; they just indicate that the shape of Janʼs face resembles a round shape. The adverb vrij indicates that Janʼs face just vaguely resembles a round shape, and zeer indicates that it comes close to being round. In other words, there is no scale of roundness implied, but we are dealing with several sets that properly include each other as indicated in (106). In order to avoid confusion, note that the circles in this graph indicate sets , and do not represent the geometrical shapes.

|

The discussion above has shown that, as far as the intensifiers are concerned, we can in principle maintain the assumption that the notions scalar and gradable are interchangeable, provided that we assume that vrij and zeer can be used both as intensifying and as approximative adverbs. If we take the comparative and superlative forms in (104b) into consideration, things become more intricate, though. Consider the examples in (107).

| a. | Jan is groter dan Marie. ⇏ | Jan is groot/niet groot. | |

| Jan is bigger than Marie | Jan is big/not big |

| b. | De eettafel | is ronder | dan de salontafel. ⇏ | De eettafel | is rond/niet rond. | |

| the dining table | is rounder | than the coffee table | the dining table | is round/not round |

Example (107) with the scalar adjective groot'big' implies neither that Jan is big, nor that he is small: as long as Marie is placed to the left of Jan on the scale of size, the statement in (107a) is true. In other words, (107a) applies to all situations indicated in (108).

|

Similarly, example (107b) provides no clue about whether the dining table is round or not (although it does imply that the coffee table is not round). This can be illustrated by means of the figure in (106). If the dining table is part of the set denoted by the adjective rond 'round' , and the coffee table is only included in the larger set denoted by zeer rond , the sentence in (107b) is true. But this is also the case if the dining table is part of the set denoted by zeer rond , and the coffee table is part of the set denoted by vrij rond . Consequently, no inference can be made on the basis of (107b) concerning the shape of the dining table.

If one still wishes to maintain that the terms scalar and gradable are the same, one has to assume that there are two types of comparatives (and superlatives, but we will not discuss this here), just as in the case of the adverbs vrij and zeer . Since we have just seen that we cannot appeal to the logical implications to determine whether we are dealing with a gradable adjective or not, we have no other option than to claim that we are dealing with gradable adjectives if the comparison can be expressed by means of a scale. However, this would run into problems with absolute adjectives like leeg 'empty' and vol 'full' . As was discussed in Section 1.3.2.2, sub I, these adjectives denote the boundaries of the scale in (71), repeated here as (109).

|

Nevertheless, an example such as (110a) can be represented as in (110b), in which the comparison is represented by means of a scale. As a result, we would have to conclude that the adjectives leeg and vol are gradable, contrary to fact.

| a. | Mijn fles | is leger | dan de jouwe. | |

| my bottle | is emptier | than the yours | ||

| 'My bottle is emptier than yours.' | ||||

| b. | Scale of “fullness" | |

|

The discussion above has shown that identification of the notions scalar and gradable gives rise to terminological confusion. Therefore, we will from now on use the opposition between scalar and absolute adjectives. The term gradable adjective will be used in its traditional sense for any adjective that can be combined with approximative adverbs such as vrij'rather' or zeer'very', and undergo comparative/superlative formation.

This subsection discusses a semantic distinction that is independent of the distinction between scalar and absolute adjectives. Some adjectives, such as boos'angry' or ziek'ill', express a transitory (stage-level) property of the entity they modify, whereas others, such as intelligent, denote a more permanent (individual-level) property. This distinction seems to be syntactically relevant in several respects. The stage-level predicates, for instance, (i) can be used in expletive, resultative and absolute met-constructions like (111a-c), (ii) allow the copula worden'to become', and (iii) can be combined with a time adverb such as vandaag; these patterns lead to odd results in the case of individual-level adjectives.

| a. | Er | is | iemand | ziek/??intelligent. | |

| there | is | someone | ill/intelligent |

| b. | De spaghetti | maakte | Jan | ziek/??intelligent. | |

| the spaghetti | made | Jan | ill/intelligent |

| c. | [Met Jan ziek/??intelligent] | kan de vergadering | niet | doorgaan. | |

| with Jan ill/intelligent | can the meeting | not | take.place |

| d. | Jan wordt | ziek/*?intelligent. | |

| Jan becomes | ill/intelligent |

| e. | Jan is vandaag | ziek/*intelligent. | |

| Jan is today | ill/intelligent |

The examples in (112) show that some individual-level adjectives are derived from (simple) stage-level adjectives by means of affixation with -(e)lijk. This is clear from the fact that these adjectives seem to denote a defining property of the modified noun phrase.

| a. | Jan is arm. | 'Jan is poor' |

| a'. | Jan is armelijk. |

| b. | Jan is bang. | 'Jan is afraid' |

| b'. | Jan is bangelijk. |

| c. | Jan is ziek. | 'Jan is ill' |

| c'. | Jan is ziekelijk. |

| d. | Jan is zwak. | 'Jan is feeble' |

| d'. | Jan is zwakkelijk. |

Furthermore, the examples in (113) show that the derived adjectives in the primed examples behave just like the adjective intelligent in (111).

| a. | ?? | Er is iemand ziekelijk. |

| b. | ?? | De spaghetti maakte Jan ziekelijk. |

| c. | ?? | [met Jan ziekelijk] kan de vergadering niet doorgaan |

| d. | *? | Jan wordt ziekelijk. |

| e. | *? | Jan is vandaag ziekelijk. |

Note that affixation with -elijk occasionally gives rise to a change in the semantic selection properties of the adjective: whereas the simple adjective lief'sweet' typically denotes a property of animate beings, the derived adjective liefelijk is applied to non-animate objects like houses, landscapes or paintings.

| a. | Jan/%Het huis | is lief. | |

| Jan/the house | is sweet |

| b. | Het huis/%Jan | is liefelijk. | |

| the house/Jan | is charming |

Note also that not all adjectives derived by -elijk are individual-level adjectives; this affix also derives adjectives that are used as adverbs. An example is the adjective rijkelijk in (115), which is mainly used as a kind of degree adverb; it sounds rather marked if used in attributive position (although many instances of this use can be found on the internet) and gives rise to a severely degraded result if used in predicative position. We refer the reader to Chapter 8 for more examples of derived adjectives that are mainly used as adverbs.

| a. | ? | een | rijkelijke | maaltijd |

| a | rich | meal |

| b. | * | De maaltijd was rijkelijk. |

| c. | De tafel | was rijkelijk beladen | met heerlijke gerechten. | |

| the table | was richly loaded | with lovely dishes |

The stage/individual-level reading need not be an inherent property of the adjective itself, but can be determined by the context or by our knowledge of reality. Consider the primeless examples in (116). Given the fact that the adverb vandaag'today' can be added to the copular construction in (116a), the adjective grappig'funny' clearly expresses a stage-level property in this example. In (116b), on the other hand, addition of vandaag gives rise to an odd result, apparently because erg grappig'very funny' is not considered to be a transitory property of books; after all, books do not change in this respect over the course of time. Accordingly, the adjective grappig can be used in an expletive copular construction if the subject is +animate but not if it is -animate, as is demonstrated in the primed examples in (116).

| a. | Jan was vandaag | erg grappig. | |

| Jan was today | very funny |

| a'. | Er | was iemand | erg grappig | (vandaag). | |

| there | was someone | very funny | today |

| b. | % | Het boek | Bezorgde ouders | van Gerard Reve | was vandaag | erg grappig. |

| the book | Worried Parents | by Gerard Reve | was today | very funny |

| b'. | % | Er | was een boek | erg grappig | (vandaag). |

| there | was a book | very funny | today |

For completeness’ sake, note that example (117) is perfectly acceptable, provided that we are discussing the episode of the comedy series Mr. Bean that was broadcast today. This does not imply, however, that being funny is a transitory property of a comedy; the adverbial phrase vandaag'today' functions to identify a certain episode, and does not imply that we are dealing with a stage-level property; being funny can simply be seen as an individual-level property of the intended episode.

| De komedie Mr. Bean | was vandaag | erg grappig. | ||

| the comedy Mr. Bean | was today | very funny | ||

| 'Todayʼs episode of Mr. Bean was very funny.' | ||||